'Hugs are not enough': Mexico’s Jesuits, Catholic bishops call for new security strategy after two priests slain

Two elderly Jesuits were murdered in their parish sheltering a person being pursued by a gunman. Catholic leaders are urging a new security strategy, but AMLO won't back down on 'hugs, not bullets'

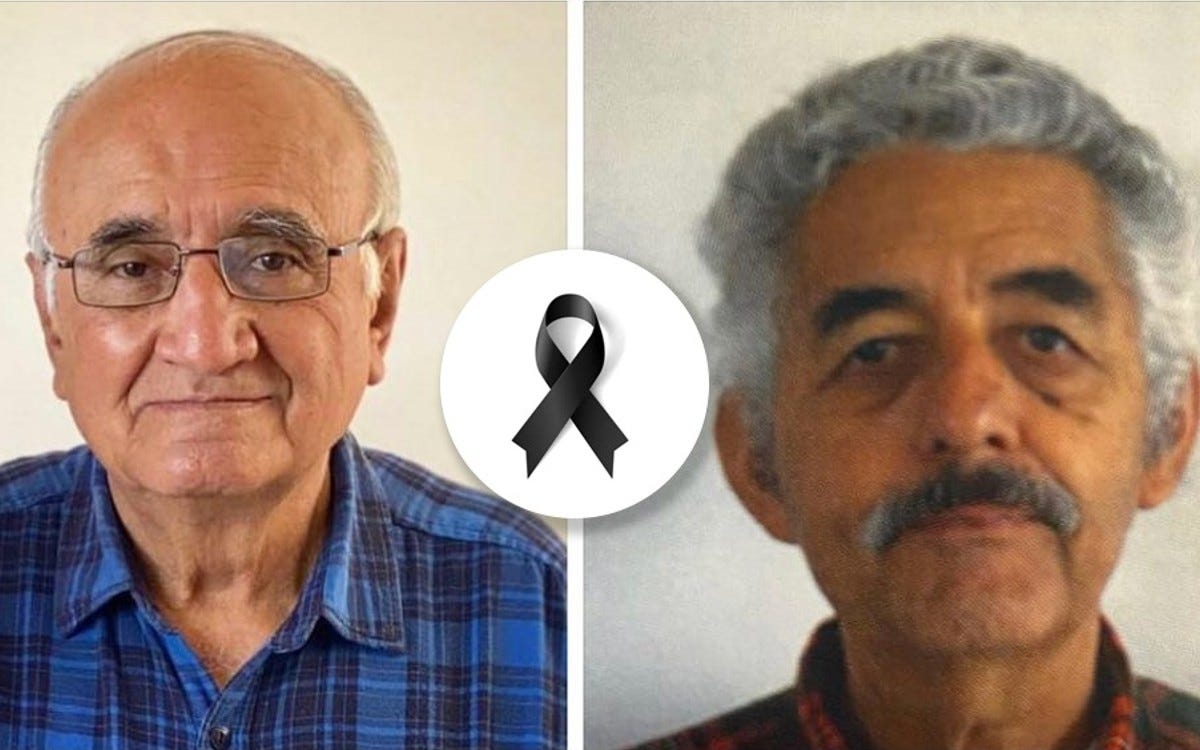

MURDERED JESUITS

A pair of Jesuit priests were murdered in their parish in the rugged Copper Canyon on June 20 as they provided sanctuary to a person being pursued by a gunman.

Jesuit Fathers Javier Campos Morales, and Joaquín César Mora Salazar – ages 81 and 79 respectively – were shot dead, along with the person being pursued, inside their parish. The person seeking refuge in the parish was later identified as Pedro Palma, a tour guide, who was kidnapped from a hotel in the community of Cerocahui.

Palma reputedly fled his captors and tried hiding in the church, where he was shot dead. One of the priests immediately rushed to provide “spiritual attention,” according to Father Javier Ávila, an oft-outspoken Jesuit on insecurity in the sierra of Chihuahua state. Ávila told the newspaper Reforma:

“One of the priests immediately approached him as a priest to provide spiritual aid. And at the moment he was providing him with spiritual services, this person shot and killed him.

“The other priest approached the criminal – someone he knows; he knows him because he is the (crime) leader of that region – to calm him down. (The priest) told him ‘take it easy,’ and he also killed him. Another priest arrived. … He didn’t do anything, but (the priest) said ‘do you know what you’ve done?’”

Father Ávila, known widely as “Padre Pato,” said previously in a message spread on social media June 21 that the suspect was a notorious crime boss called “El Chueco” – the twisted one – who is also implicated in the 2018 disappearance of an American tourist. He said in the message shared by journalist Marcela Turati:

“When they called me from Cerocahui to tell me that ‘El Chueco,’ head of the local criminals, just killed Javier Campos and Joaquín Mora, both brother Jesuits, I had to silence them because there were threats against the (Jesuits).”

The priests’ bodies were taken from the parish by the assailant and founded June 22, according to Chihuahua officials. The Jesuits confirmed the priests’ identities the following day.

“Acts like these are not isolated. The Sierra Tarahumara, like many other parts of the country, confronts conditions of violence and neglect which have not been reversed. Every day, men and women are arbitrarily deprived of life as our brothers were murdered,” the Jesuits’ Mexican province said in a June 21 statement.

Mexico’s Jesuit university rectors offered a more dire assessment of the country. The rector of the Iberoamerican University in Torreón said of the situation:

“When the state does not have territorial control and allows independent armed groups to control it, we call that a failed state. Mexico has been controlled like this for many years and the state is absent.”

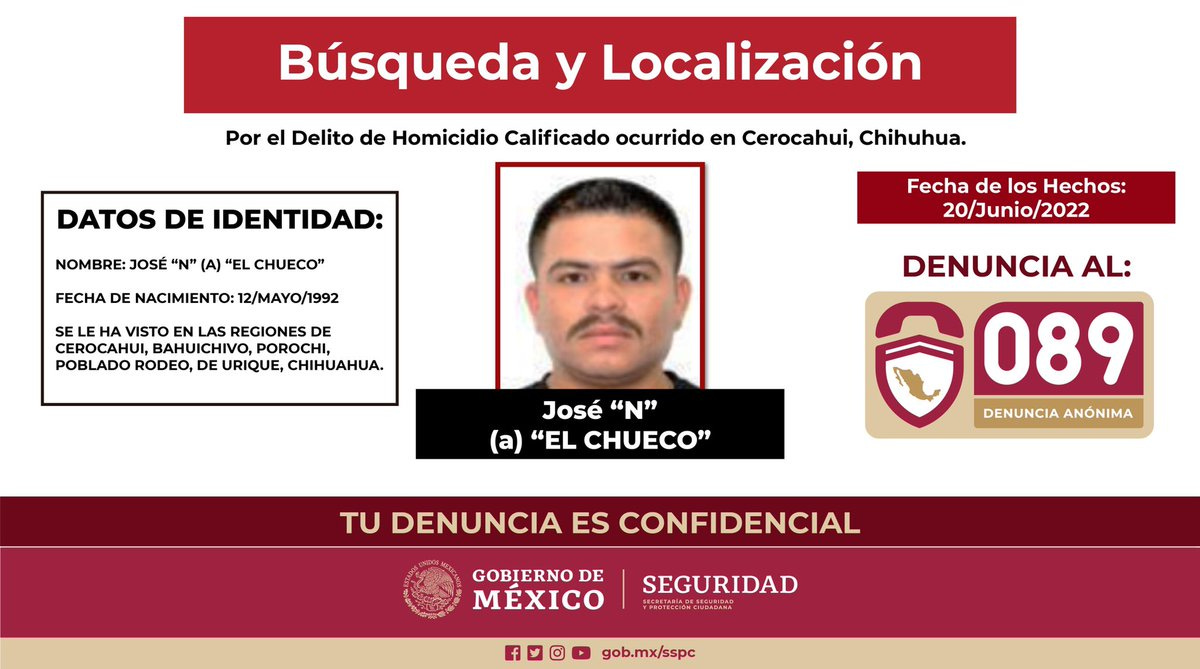

‘EL CHUECO’

Mexican officials named local crime boss José Noriel Portillo Gil “El Chueco” as a suspect in the slayings and issued a 5 million peso reward. El Chueco has terrorized parts of the Sierra Tarahumara for years – to the point his name is not spoken by locals. The vicar of the Diocese of Tarahumara spoke of the fear in an interview with radio host Carmen Aristegui, saying they stayed silent for six hours after the attack to protect the survivors of the attack.

El Chueco reputedly controls the crime territory around Cerocahui for “Los Salazar,” a group linked with the Sinaloa Cartel. Federal officials have floated the hypothesis that a dispute between Los Salazar and “La Linea” – an armed group originally aligned with the Juárez Cartel – resulted in the 2019 attack on nine women and children from a community of bi-national mormons in neighbouring Sonora state. (The victims’ families insist the killings were premeditated.)

El Chueco is also accused in the murder of American tourist Patrick Braxton-Andrew, a teacher from North Carolina, who was an experienced traveler in Latin America. Braxton-Andrew set out hiking in the municipality of Urique in October 2018 and was never seen again.

A BASEBALL DISPUTE TURNS DEADLY

Chihuahua state prosecutor Roberto Fierro said June 22 that El Chueco was involved in an altercation prior to the Jesuits’ murders. Witnesses, according to Fierro, said El Chueco abducted two individuals prior to the parish murders and burned down their home. He was reputedly irate because of a dispute arising from a baseball game, in which one of the teams supposedly sponsored by El Chueco lost. Those two local individuals are presumed missing and are not tourists as originally reported, according to the prosecutor.

El Chueco later kidnapped and killed Palma, the tour guide, and then the priests. A source in the Jesuits says El Chueco was likely drugged up while carrying out his crimes; he knew the priests, who had spent 34 and 23 years respectively in the Sierra Tarahumara. Father Ávila told Imagen Radio that El Chueco was baptized by Father Campos.

A RUGGED REGION RIFE WITH CARTEL VIOLENCE

The Copper Canyon – a series of canyons – is a region of rugged beauty, rife with drug cartel activities. Drug cartels have long disputed routes through the canyons – served by a train connecting Los Mochis, Sinaloa, near the Pacific coast and Chihuahua city – and criminal groups carry out activities such as illegal logging. As the newsweekly Proceso noted in a recent story: “The defense of the communities in the Sierra Tarahumara is concentrated in the struggle against illegal logging.”

A Canadian source in Chihuahua, who moved to the state with a NAFTA initiative on forest management and restoring the watershed (which feeds the Rio Grande River), said in 2007 that the initiative was scuttled by rampant illegal logging and the failure of state and federal authorities to intervene.

The Jesuits have worked in the canyon for centuries, serving the local Raramuri (also known as Tarahumara) communities. Some have been outspoken – like Father Ávila, known locally as “Padre Pato.” Father Ávila loudly denounced the August 2008 massacre of 13 people at a party in Creel, a jumping off point for trips into the Copper Canyon. The slaying is considered the first such massacre in Mexico’s unrelenting bloodletting since then-president Felipe Calderón ordered a crackdown on drug cartels in December 2006. Father Ávila subsequently received state police protection.

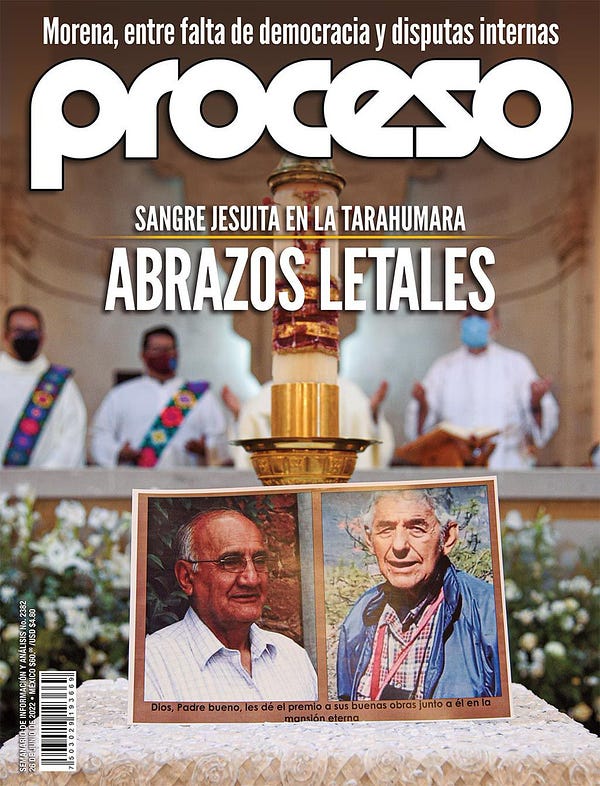

“HUGS ARE NOT ENOUGH TO STOP BULLETS”

At the funeral Mass for Fathers Campos and Mora, Jesuits denounced the deteriorating security situation in the Sierra Tarahumara and the country country as a whole. They also asked for a revision of the president’s stated security strategy of “hugs, not bullets.” In his homily, Father Ávila said of the strategy:

“Hugs are not enough to stop bullets. … I respectfully ask the President of the Republic to review his public security project, because we are not doing well. This is popular clamor. This is not an isolated event in our country, a country invaded by violence and impunity.”

The Mexican bishops’ conference – a group traditionally reticent to criticize the president, though not considered close with President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) – also asked for a revision of the “hugs, not bullets” security strategy, saying in a statement:

“It’s time to review security strategies that are failing. It is time to listen to citizens, to the voices of the thousands of relatives of victims and of the murdered and disappeared (and) the police officers killed by criminals.

“We believe it is not useful to deny reality and blame the past for what we have to resolve now. Listening to each other doesn’t make anyone weak; to the contrary, it strengthens us as a nation.”

PRESIDENT PROMISES MORE HUGS

AMLO rejected any suggestions of changing policy – doubling down, again, on “hugs, not bullets.” He also doubled down on his standard responses to atrocities in the country: blaming the past and portraying himself and his movement as the true victims.

“No, we’re not going to modify the strategy,” AMLO said after the slayings. “The human being is not bad by nature: circumstances lead them to take the path to antisocial behavior. We believe in rehabilitation and we do not think that people have no other destiny than to be eliminated.”

He took aim at the bishops, who hadn’t been especially vocal on security matters until the Jesuit slayings – though speaking out loudly on issues such as abortion (decriminalized by Mexico’s Supreme Court in September 2021) and occasionally immigration, on which they have criticized the AMLO administration’s willingness to go along with U.S. measures such as Remain in Mexico and Title 42. AMLO – who church officials admit they don’t have a close relationship with – blasted the bishops (and the Jesuits) on Jan. 27, saying:

“Our adversaries, with their spokesmen and lackeys, try to confuse, disinform, manipulate, saying, ‘How barbarous, there’s never been such violence in Mexico like there is now,’ but it’s not true. … All of this is forgotten [the atrocities of previous administrations] including for the religious, who, with total respect, are not following the example of Pope Francis because they are acting in cahoots with to the Mexican oligarchy.”

He amped up the rhetoric further, saying:

“What they propose is very irrational. They have also defended a failed strategy. …What do they want, that we go back to machine gunning people from helicopters?”

The president also wondered aloud why anyone would accuse him of acting in cahoots with the Sinaloa Cartel, defending – not for the first time – his encounter with the mother of imprisoned cartel boss Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán. He also again raised the alleged connections between the cartel and former public security secretary Genaro García Luna between 2006 and 2012. (García Luna, is charged in New York on accusations of taking bribes from the Sinaloa Cartel. Recent court filings allege he “subjected a journalist to a ‘campaign of harassment & threats’ between 2008 and 2013 and, “In 2009 or 2010, he bribed a news org to prevent ‘negative stories about him.’”)

“What about the alliances with the Sinaloa Cartel and the evidence that I greeted Guzmán Loera’s mother? Imagine that kind of journalism. We have principles, we have ideals.”

AMLO’s response touched on recurring themes for the president such as being “humanist” – humanista, in Spanish – using a soft touch with organized crime and blaming everything on the past. But it also belied the gap between his rhetoric and reality: his administration has discarded early proposals from experts and activists, along with people in his own campaign and outside observers, who wish-cast expectations of pacifying the country and ending the war on drugs – and that the government pursue novel policies such as restorative justice and and replacing soldiers with properly-trained police. Security analyst Alejandro Hope pointed a gaping gap in the rhetoric versus reality, tweeting, “

“Could (the president) cite some federal ‘rehabilitation’ program implemented by the current administration and whose results have been evaluated by an independent institution?”

THE MOST MURDEROUS COUNTRY FOR CLERGY

The Jesuit slayings reinforced Mexico’s reputation as one of the world’s most murderous countries for Catholic clergy. At least Mexican seven priests have been killed since December 2018, when President Andrés Manuel López Obrador took office, according to the Catholic Multimedia Center in Mexico City. But the slaying of clergy has stained Mexico for much of the past two decades.

Church observers and clergy offer no clear hypothesis for the scandalously high number of slain priests in what is still the world’s second most populous Catholic country with 77% of the population professing the Catholic faith.

But the relationship between criminals bosses and clergy can be complicated. Priests working in conflictive regions know the rules, according to interviews with Catholic and Protestant clergy. Jesuit Father Jorge Atilano, who designed a program for repairing the social fabric in rough parts of Michoacán state, said of the murdered Jesuits in the Sierra Tarahumara:

“The Jesuits had a certain authority, they knew how to fit in and get along, they’ve learned to live in insecure areas … learned the codes: what to say, what not to say, never accepting favors, not breaking relations, being friendly.”

“The position has been one of respect and inclusion, to be able to stay in these places, not to speak against them, but not to cover things up. It has been learning to live together, while having limits.”

Bishops in many of the dioceses in regions rife with drug cartel activity prefer to stay silent – sometimes for safety concerns. Bishop Salvador Rangel, former leader of the Chilpancingo-Chilapa diocese in Guerrero, has been an exception. He’s known for brokering deals among drug cartel bosses to calm conflictive regions in Mexico’s heroin-producing heartland, but says many of this brother bishops have been timid.

“We have lacked a stronger response as bishops because, unfortunately, every day organized crime is increasing its presence, gaining more authority, taking over more of the states, municipalities, institutions. … I have denounced all of this and many bishops tell me, ‘Look, unfortunately we can’t do what you do but we support you.’ There are bishops who do not denounce this.”

CLOSE CHURCH-STATE TIES

Some of the timidity comes from Mexico’s unhappy relationship of strained church-state relations – in which priests were persecuted and the Vatican and Mexican state were officially estranged. Church leaders have subsequently pursued close and cordial relations with local and state leaders – and seen outspoken priests and prelates, along with religious orders advocating for human rights and democracy and condemning corruption, as troublesome.

Sources in several dioceses in the states of Michoacán and Chihuahua have spoken of state governors providing vehicles to bishops in their states, whose public comments on security and corruption are subsequently subdued. The newspaper La Jornada revealed the government of Mexico state – which has been controlled by a political clan, which produced former president Enrique Peña Nieto – paid catechists in various dioceses, where bishops stayed mum on corruption and vices such as femicides.

Some dioceses become targets of unwanted attention for relations with crime bosses and their families. The Archdiocese of Tulancingo in Hidalgo allowed the construction of a chapel sponsored by Los Zetas founder Heribero Lazcano. The chapel features a plaque recognizing Lazcano’s patronage. The Diocese of Culiacán – which seldom speaks out on issues of violence – closed the local cathedral in 2020 for the marriage of El Chapo’s daughter to the son of another crime family.

NARCOS CONSIDER THEMSELVES PROPER CATHOLICS

Suspicions of drugs alms also abound, along with prelates suggesting publicly that drug money could somehow be cleansed though the collection plate. The bishop of Celaya in central Guanajuato state had to deny allegations of drug alms after the 2020 capture of José Antonio Yépez Ortiz – leader of the Santa Rosa de Lima Cartel and known as “El Marro” or the sledgehammer. El Marro was notorious for his altars to Our Lady of Guadalupe – even as his cartel killed police across Guanajuato, stole and fenced gasoline siphoned from Pemex pipelines and fought off incursions from the Jalisco New Generation Cartel.

Priests say narcos often present themselves as godparents – creating complications at baptisms. Then there the families, according to Father Larios:

“Generally, a narco’s wife is very devout. You’ll notice a narco’s mother is very Catholic.”

POWER PLAY?

The motives of narcos for approaching priests can be complicated – and even involve requests for blessings for illegal activities or even their new weapons. Father Omar Sotelo, director of the Catholic Multimedia Center in Mexico City – which tracks the murders of priests – described a complex panorama of popular piety and power in an interview with Catholic News Service in 2019:

“Many of the people who make up these groups, these cartels, have this custom or this way of approaching (the church) to seek protection. (But) the pastor, being in some way a figure of spiritual power, who offers services ... who protects the community, tends to be sort of seen as competition for these groups.”

The murder, Father Sotelo said, sends the message: “If I’m able to kill a priest, I can kill anyone.”

One cartel in control = less crime?

President López Obrador speaks for two hours (or more) every weekday at 7 a.m. in a press conference called “La Mañanera.” He often meanders and spitballs and sort of responds to questions – though, mostly, it’s two-hours of trolling. He often says the quiet part out loud – such as his assertion that regions with a single drug cartel or criminal organization in control enjoy better security. He said June 15:

“There are places where a strong (criminal) group is predominant and there are no clashes between groups. That’s why there are no homicides. Let me explain further: Sinaloa and Durango are not among the states with the most homicides because there is only one gang and in Michoacán, there is not only single group, rather 10 (different groups) and the confrontation between the groups are greater.”

The one group dominating Sinaloa and Durango states is the Sinaloa Cartel – a criminal organization AMLO has never publicly criticized and even appears at ease with. The comments come as AMLO travels carefree through the rugged Sierra Madre Mountains of Durango and Sinaloa states – a region in which reporters covering his most recent tour there reported being stopped at an illegal checkpoint manned by presumed cartel gunmen.

The comments also come as analysts express suspicions AMLO is somehow pining for a time in past decades when politicians made deals with drug cartels to keep violence to a minimum in exchange for tolerance of illegal activities.

PAX NARCA?

Writing in the newspaper El Financiero, security analyst Eduardo Guerrero pondered if AMLO was pursuing a pax narca, noting: “Up to a certain point, the president’s words simply reflect reality.” But he continued:

“The president’s words also lead to the question [asked during his June 22 press conference] of whether what is sought is an agreed peace. In response, AMLO limited himself to reiterating his hypothesis. ‘It is the predominance of a group that has no competition with others which leads to no confrontations.’ In other words, the president did not deny that an agreed peace is being sought.”

That assertion that multiple criminal groups disputing crime territories would cause an uptick in violence is not disputed. A study earlier this year by the International Crisis Group showed a criminal landscape fragmenting over the past dozen years – with 543 criminal groups having operated or continuing to operate. “Fragmentation drives violence,” said Falko Ernst, senior Mexico analyst for the International Crisis Group. But he said of the president’s seeming preference for a single criminal group in control:

“The question is whether that’s politically, morally – in terms of a project of state –defendable if you allow that to happen or try to pursue that. From what I’ve observed – not only in Sinaloa, but in other regions of the country – this has been an aspiration of this administration, but they have so far largely failed to successfully implement informal forms of order that could in some areas include betting on one group or another because there has been no coherence to their overall strategy.

“Sinaloa to some degree seems to be really the exception in that you have something much more coherent and hierarchically (in) structure – relatively speaking in comparison to other areas – to negotiate with.”

NO CHICKEN IN CHILPANCINGO

Chicken stands in one of the main markets in Chilpancingo – capital of Guerrero state – closed abruptly after a series of slayings targeting suppliers. According to Insight Crime, a distributor was murdered at the market June 6. Three days later, two employees of another distributor were attacked in the parking lot – with one of them perishing. Then, on June 11, gunmen burst into a chicken farm near Chilpancingo and executed six workers. A 12-year-old girl was among the victims.

Former local bishop, Salvador Rangel – who intervened as a mediator in the chicken-extortion crisis – blamed the situation on rival gangs disputing extortion rackets in Chilpancingo. But the shortage of chicken there reflected a broader escalation of extortion across Mexico as criminal groups extract criminal rents from captive local populations. In San Cristobal de las Casas, earlier in June, an estimated 100 thugs on motorcycles (from one of the various gangs known as motonetas) terrorized the neighborhood around a market they were fighting for control of.

In Quintana Roo state, cartels have turned battled over drug dealing turfs in Cancún, Playa del Carmen and Tulum. But local journalist Vicente Carrera, publisher of Noticaribe in Playa del Carmen, said extortion is rife in the region, too – with businesses being attacked or closing for non-payment. The situation reached such a level that people selling roast chickens in poor neighborhoods were being extorted.

“That tells you how it has gotten out of control because right now it’s not only the strong narco groups engaged in extortion, but also beginners, criminals who suddenly start extorting in the park, the corner store, the people selling chickens, selling fruit. It’s this kind of extortion reaching all levels.”

RECORD YEAR FOR EXTORTION

Rangel described a situation in Chilpancingo and central Guerrero of criminal groups aggressively getting into extortion as the profits from growing opium poppies and producing heroin vanished – with fentanyl displacing it. “(Poppies) is no longer a business for them so they get into extortion, taxing meat, beer, bread, everything, even tortillas.” Their reach also includes municipal governments, with at least four being extorted directly by criminal groups, according to Rangel. “The municipal budget goes to the narcos,” he said.

Extortion in Mexico reached record extortion levels in May, according to the newspaper El Universal – with criminal groups imposing illegal taxes on everything from limes to avocados to markets to Catholic parishes. The Secretariado Ejecutivo del Sistema Nacional de Seguridad Pública (SESNSP) recorded a 28.8% increase in extortion in May over the same period of 2021. Analysts expect the problem to worsen “because the (government) doesn’t invest a single penny in the problem,” Alejandro Hope told El Universal.

Extortion is also changing the criminal landscape – with groups extracting rents from previously unattractive territories, according to Falko Ernst.

(It’s) game that is not characterized by holding territory, fighting for territory, holding that territory. (It’s) a space within which you can just by providing violence and threat and the appearance of protection as the counterpart thereof extract resources from any economic activity. That’s exactly what’s been going on

“If you don’t react to extortion economies by introducing institutional bulwarks, by cutting ties between state and crime, the whole reform package you would have to implement, there’s almost endless growth for this model of criminal control and criminal financing and also the financing of criminal disputes … because you don’t need to have an area that’s attractive or stands out by having a concentration of natural resources.”

LYNCHING SHOWS LACK OF STATE MONOPOLY ON USE OF VIOLENCE

Daniel Picazo got lost driving through the town of Papatlazolco in the Sierra Norte of Puebla. A young lawyer and political adviser working in Congress, he visited Puebla frequently as his family had a property in a picturesque part of the state. But he apparently got lost in Papatlazolco, just a rumours were circulating on WhatsApp of supposed child abductors. Even worse, he was driving a van – as an alleged child abductor supposedly had earlier.

Picazo, 31, was beaten by a mob – which reputedly included the mayor – and set on fire. In Mexico, it’s called a ‘linchamiento” and occurs with disturbing frequency in the insular communities of the country’s central states. El País wrote of the situation:

“The scene of the crime is a town beset with suspicion because, people say, the authorities have done nothing about the rapists, thieves, and criminals that have plagued the community for years. They are accustomed to taking the law into their own hands, and the justice system had never acted against the lynch mobs either. But the higher profile of this particular victim, a political advisor to the Mexican legislature, seems to have finally awakened the criminal justice system.”

In its chilling account, El País (translated into English) noted local and state police walked behind the mob, but did not intervene – except to verify some identifications he pulled from his wallet in a last ditch attempt to save himself.

“The videos show Daniel, bloodied and handcuffed, being dragged along by some men and followed by a mob. A police van trails behind, like an official escort to the lynch mob.

“The police took pictures of those documents [produced by Daniel] but did nothing to stop the beating and let the mob set Daniel on fire a second time. The kneeling body fell forward and was consumed by the bonfire. Some of the eyewitnesses said the detained suspects have killed before, but were never brought to justice for those crimes. Other suspects have left town fleeing the law.”

A HISTORY OF LYNCHINGS

Nine suspects have been arrested for the Picazo murder. Most cases go uninvestigated and unpunished, according to investigators. El País cited a study from the Iberoamerican University in Puebla city, which documented 78 people being lynched in Puebla state between 2015 and 2019, along with 599 attempted lynchings. The study’s author, Tadeo Luna, attributed to the rising number of lynchings to “absent government and social stress caused by specific events in daily life [which] are driving this increase in lynchings [and] are becoming part of the social imaginary as a legitimate form of defense against lurking dangers.”

But another academic, historian Gema Kloppe-Sanatamaría, who studied lynchings for her doctoral thesis, attributes the willingness of people taking violence into their own hands to a history of the Mexican state not exercising a monopoly on the use of violence.

In a separate interview with El Pais, she highlighted the supposed “pax priísta” (PRI peace) which emerged during the post-Revolution years, in which the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) and its various incarnations ruled consecutively between 1929 and 2000. Kloppe-Santamaría’s research, however, showed lynchings were common at the time, belying the idea of a PRI peace.

“Speaking of this phenomenon [of lynching] does not signify a failed or absent state. They’re part of the way in which authority in Mexico was shaped.”

She continued:

“In Mexico, the authorities never claimed a monopoly on the use of violence. They always sought to delegate it to the local level, with parastatal actors or abusive local authorities, allowing extralegal violence to be used by a multiplicity of actors.

“The PRI State never sought to monopolize violence, it sought to manage it, domesticate forms of violence that threatened the political project of a hegemonic party, but not eliminate them. The way the lynchings have been read is, ‘well, this illustrates the absence of the State, there are not enough police, or presence of the State or it is the State is in crisis.’ But, no, this is part of a long historical trajectory of how the negotiations between the State and citizens have been in terms of how justice is administered.”