'It’s a matter of perceptions'. Why migrants converged on Ciudad Juárez and El Paso

Migrants arrived in the border cities of Ciudad Juárez and El Paso in record numbers in 2022 with some clinging to the idea 'it's easy to cross.'

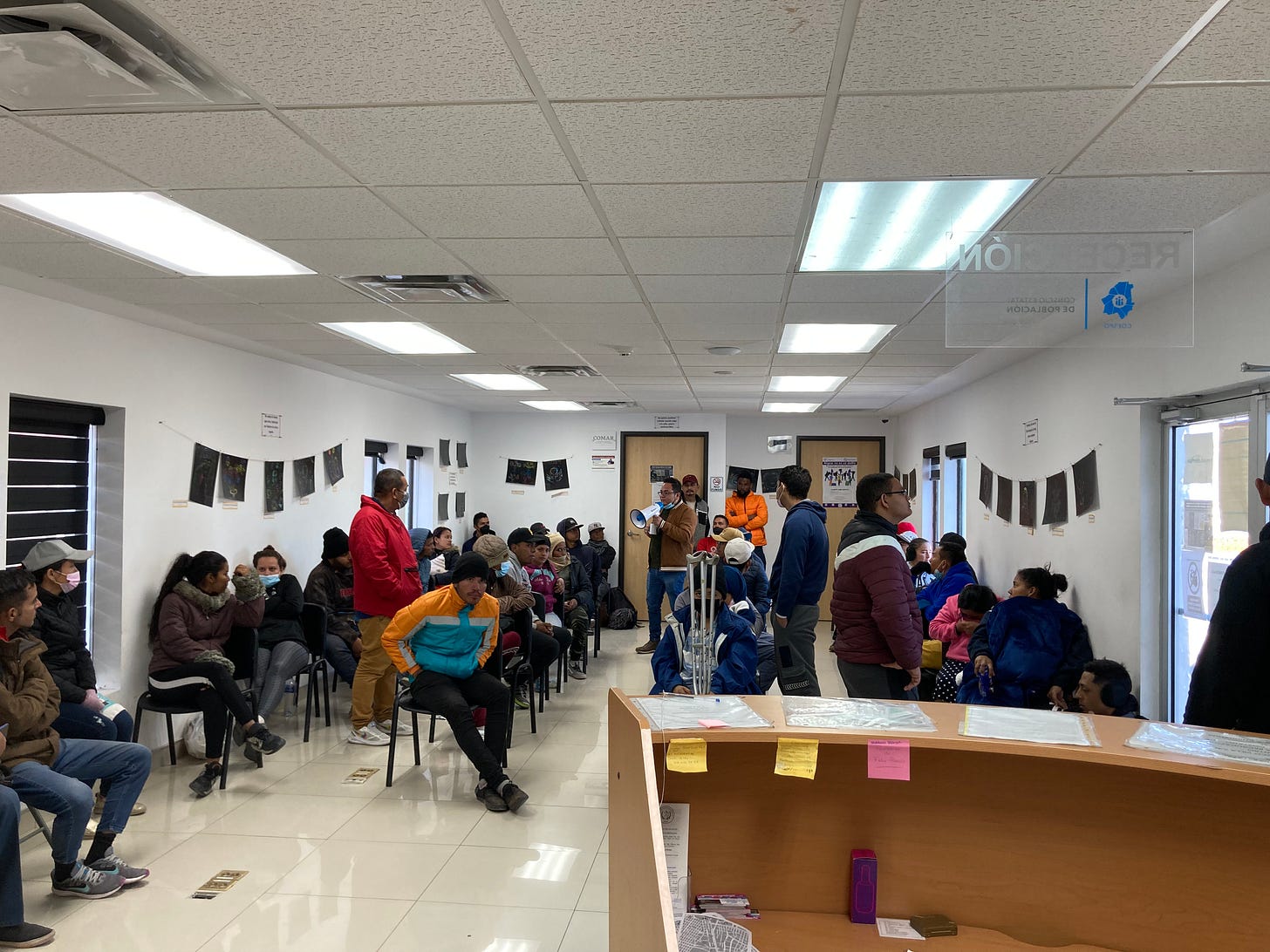

Migrants cued early on a chilly January morning outside the State Population Council (COESPO) office by the Paso del Norte border bridge separating Ciudad Juárez and El Paso, Texas. Once inside, a staff member oriented them on the border, urging a group of them not to cross illegally and exhorting them to consider options for staying on the Mexican side. A legal advisor, meanwhile, worked with another group on getting registered for border arrival appointments via the CPB One app – unsuccessfully as the system was swamped with requests.

Most of the migrants seemed intent on crossing to the United States – or Canada if the option were available. Staying in Mexico was a non-starter, according to a Venezuelan woman, who was seeking advice with her husband and toddler son.

“They put a lot of obstacles for us to get here, so Venezuelans don’t like Mexico,” she said while waiting. “They have treated us badly here. … The reality is that officials treated us badly. And the cartels: They kidnapped us, coming up here. So, yes, Mexico is extremely dangerous.”

Migrants in unprecedented numbers transited Ciudad Juárez and crossed into neighbouring El Paso over the latter half of 2022 – with Venezuelans, Nicaraguans and Cubans making up much of the northward flow. U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) reported 251,487 encounters on the Southwestern Border in December – an all-time monthly high. CBP’s El Paso Sector registered 55,747 encounters in December, also a record tally.

Images of migrants wading across the Rio Grande River toward El Paso went viral, while images of people sleeping in the streets and shivering in cold made international news. CPB encountered as many as 9,000 migrants daily during December, according a dispatch in the Dallas Morning News.

Mass crossings drew attention, too – with a caravan made up mostly of Nicaraguans starting out some 500 miles south in Torreón and arriving at the border in buses provided by a Chihuahua state mayor. The migrants were offered places in local shelters, but opted to instead head straight for the river, according to people familiar with the caravan.

The record numbers preceded a Jan. 5 announcement from the Biden administration to expand Title 42 to arrivals from Haiti, Nicaragua and Cuba – joining Venezuelans, who were added to the pandemic-era program Oct. 12. The administration also expanded its humanitarian parole initiative – which was originally designed for Ukrainians, but extended to Venezuelans – allowing 30,000 migrants from the four countries to arrive in the United States so long as they had sponsors and hadn’t passed through Panama or Mexico. As reported previously in this newsletter, “Mexico agreed to accept 30,000 returnees from those countries ‘who fail to use these new pathways.’”

U.S. and Mexican officials have been quick to call the measures successful. Reuters reported:

“U.S. authorities encountered a daily average of just 115 migrants from those countries [Haiti, Nicaragua, Cuba and Venezuela] over a week-long period ending on Jan. 24, down from a 7-day average of 3,367 in the week to Dec. 11, a 97% drop, DHS said.”

Dallas Morning News cited a U.S. Border Patrol spokesman, saying the number of migrants arriving in the El Paso Sector dropped in January to 929 per day from more than 2,100 in December.

Why did migrants descend on Ciudad Juárez/El Paso?

President Joe Biden visited the border at El Paso on Jan. 5 – a trip covered in the previous edition of this newsletter. El Paso residents reported a clean up of the city prior to the president’s arrival with migrant encampments cleared. Ciudad Juárez residents reported a surge of more than 200 National Immigration Institute (INM) agents arriving in the city and stepping up enforcement, too. The INM christened the surge “Juárez-El Paso Contention,” while commissioner Francisco Garduño Yáñez called its timing “a coincidence.”

No one on either side of the border could explain why migrants turned their attention to the Ciudad Juárez-El Paso corridor – with observers saying it followed a pattern of migrants picking parts of the of the border based on word-of-mouth, perceptions of safety and ease of entry, and coyotes (smugglers) trying to drum up business. It also followed a pattern of migrants converging on specific corridors – such as Haitians in Ciudad Acuña and Del Rio, Texas, in September 2021 and large flows later passing through Piedras Negras and Eagle Pass, Texas.

“When you see flows, it’s a matter of perception,” said Victor Manjarrez, a UTEP professor and former U.S. Border Patrol sector chief.

“If you look at a map of Mexico, there are decision points (along the way.) Do I take the Gulf route, the Central mountain route, the Baja route?” He explained. “What I suspect has changed is there’s a realization by the cartels, the owners of the plaza, that there’s some money to be made here. It’s part of those decision points further south.”

Perceptions

Father Javier Calvillo, director of the Casa del Migrante in Ciudad Juárez, said staff would receive calls from shelter directors in southern and central Mexico during 2022, warning:

“‘Listen, I have Venezuelans here and they’re telling me that it’s easy to cross.’ And I would tell them, ‘No, no, no it’s not easy.’ … All of them wanted to head north, especially to Juárez due to what was happening.”

A Venezuelan migrant sleeping outside the Sacred Heart Church in El Paso’s historic Segundo Barrio offered a simple explanation for choosing to cross the border at Ciudad Juárez:

“Because it was the only information that I had. … And because, obviously, I already had a friend who had crossed through here on Jan. 1 and he was the one that told me. … I trusted him and I decided on here.”

The migrant, speaking in mid January, said he crossed the border the day before – almost immediately upon arriving in Ciudad Juárez on a commercial flight, having previously obtained a 30-day tourist visa in Mexico City. “José” – a pseudonym – crossed the border, he says, by following a group already making the trip, passing himself off as one of the people who paid to be guided across. The group squeezed through a gap in the wall, he says.

Other migrants at the Jesuit-run parish in El Paso say they either climbed over the border wall or crawled under it. “It’s not that hard if you’re young,” said a Venezuelan named Orlando, who crossed in a group of 12 by vaulting himself over the three-metre high barrier on the shoulders of his colleagues.

Title 42 knowledge

All of the Venezuelans interviewed for this report said they were aware of the changes to U.S. immigration policy Oct. 12, which extended Title 42 to them, but continued northward anyway.

A migrant who preferred not give his name says he was in Nicaragua, when he heard the news and was going to return to Venezuela or try staying in Costa Rica. But he said, “Some friends arrived and they said they would help me cross.”

José says he found out about Title 42 after being detained for five days by Mexican immigration authorities in Oaxaca state, but decided to continue anyway, hoping to reunite in the United States with his mother and sister in Florida.

Orlando says he arrived in Ciudad Juárez on Oct. 13 – the day after Title 42 was applied to Venezuelans. He crossed anyway and was deported to Tijuana. Orlando says he made his way back to Ciudad Juárez, worked there for a month as a mechanic and crossed again.

The Venezuelan couple waiting instructions in Ciudad Juárez say they were transiting the treacherous Darién Gap between Colombia and Panama when they learned of Title 42 being applied to them. They thought about staying put, “but we started hearing that the president was giving opportunities to Venezuelans, but to enter in a regular way. … One has that hope and continues onward.”

They obtained a safe passage document in Mexico and bought a bus ticket from Mexico City to Ciudad Juárez on Futura, saying the bus line operated special service to Ciudad Juárez and no other operators would not sell them tickets.

Kidnappers boarded the bus in the state of Durango and demanded $5,000 from each of the passengers. The family offered 5,000 pesos ($260), which was accepted. The migrant suspected collusion on the part of the driver and said:

“The bus drivers themselves are in cahoots with the cartels. They know that the bus is full of migrants and they agree to stop.

“We had to pay the amount that they said to be released. If you didn’t pay, they would hold everyone, lock them in a room until they called their family members to send money.”

The family eventually arrived in Ciudad Juárez and crossed the border – only to be expelled to Ciudad Juárez and bused by Mexican immigration officials to Mexico City, more than 1,100 miles south. They promptly retuned to Ciudad Juárez, riding atop freight trains in frigid temperatures.

Security in Ciudad Juárez

Ciudad Juarez ranked as the murder capital of the world between 2008 and 2012 with more than 10,000 homicides committed as cartels battled for control of a coveted corridor for smuggling drugs into the United States. The city has calmed substantially over the past decade, but experienced shocking spasms of narco-violence in recent months.

An August riot erupted in the state prison between rival groups and spilled into the streets as one of the gangs, Los Mexicles, targeted innocent bystanders.

A Jan. 1 uprising in the same prison left 19 dead, including 10 guards, as Los Mexicles members created mayhem to extract their convicted leader Ernesto Alfredo Piñon de la Cruz “El Neto.” A total of 30 prisoners escaped the notorious lockup, which federal security officials say contained 10 “VIP” cells – where Piñon continued doing business and had a safe containing 1.7 million pesos. Piñon was killed in an early morning shootout with state security forces Jan. 5, according to the Chihuahua state government.

Safe city for migrants?

State government officials in Ciudad Juárez insist the city is safe for migrants. One source said local police shaking down migrants posed more of risk than the cartels. A report from WOLA, a human rights think tank, found similar allegations of migrants being extorted by local police and National Guard members.

“The issue of the (prison) is an incident that stays there in the (prison),” said Óscar Ibañez, the state governor’s representative in Ciudad Juárez. “The rest of the city is calm.”

The sense of security of migrants comes in the context of comparisons to other border cities such as Nuevo Laredo and Reynosa – which border Laredo, Texas, and Hidalgo, Texas, respectively – where cartels routinely kidnap and extort migrants.

Enrique Valenzuela, director of COESPO, insisted, “One reason people come here is because they’ve been well-treated.” He pointed to the Remain in Mexico Program – known as Migrant Protection Protocols [MPP], where asylum seekers waited in Mexican border cities while their cases were heard in U.S. courts – saying MPP participants in Ciudad Juárez largely avoided the atrocities suffered by participants in other cities.

But incidents of violence targeting migrants is making news. (See further down).

Increasing organized crime involvement

The story of migration through Ciudad Juárez is nothing new. But officials and people working with migrants say the city mostly received deportees from the United States rather than northbound migrants. That changed in 2018 for reasons they still can’t explain. It’s evident in the rapid expansion of migrant shelters. Ciudad Juárez was home to just three shelters for migrants in 2018 – with the diocesan Casa del Migrante largely receiving returnees. Now there are more than 30 shelters – most operated by Evangelical pastors. “The faith community is the backbone” of migrant support, Valenzuela says.

As northbound migrants started to arrive in larger numbers, Valenzuela and others say gangs and drug cartels started getting involved in the business. He observed:

“It’s more lucrative to be a human trafficker than a drug trafficker.”

Ibáñez, the governor’s representative in Ciudad Juárez, added:

“There have always been polleros and coyotes and in some way they’ve always been linked to criminal groups. But now it’s one of organized crime’s main sources of income. … Trafficking persons is still cheaper. You don’t have to invest anything. You just charge them so it’s much more interesting.”

Stories of attacks on migrants have surfaced in Ciudad Juárez. Police arrested two men who shot the driver of a local bus carrying 42 Venezuelan migrants in early December. Three vehicles pursued the bus, cut it off and opened fire, striking the driver, according to investigators. Local media described the attack as possible kidnapping attempt as criminal groups fight over control of migration in the city.

Border Report quoted Chihuahua State Public Security Secretary Gilberto Loya after the attack:

“Organized criminal gangs are financing their operations through migrant trafficking. This is happening all over the state, but more so along the border. Right now, all polleros are directly linked to organized crime.”

Two suspects were arrested, but subsequently freed by a judge.

The attack on the bus followed a raid on a migrant shelter in which armed individuals burst into the church-run facility, started lining up the women and children, but fled after a patrol car passed by.

Jobs for migrants in Mexico – if they want them

Once a remote border outpost in the Chihuahua desert, Ciudad Juárez has mushroomed over the past 60 years to become Mexico’s sixth-largest municipality with a population of 1.5 million.

Both Valenzuela, the COESPO director, and Ibáñez, the governor’s representative, express sanguine opinions on migration through the region, viewing it as an opportunity to fill empty factory jobs and grow the community – if only migrants wanted to put down roots.

Valenzuela points to 3,500 openings in Ciudad Juárez maquiladoras (factories for export) and the service sector, saying COESPO and local migrant shelters can help facilitate the paperwork. “We want them to be a productive part of this community,” Valenzuela says.

But it’s a hard sell. During October and November, when Venezuelans were being returned to Mexico, he reported COESPO pitching some 2,000 migrants on working in Ciudad Juárez. Just 200 migrants accepted the offers of jobs, which paid roughly 1,800 pesos ($95) weekly, he says.

“People don’t want to see they’re just a step from the United States,” he says. “Even though they can get a job here, they don’t stay.”

Migrants interviewed for this report say they never considered staying in Mexico, citing security concerns and a desire to financially support families back in Venezuela.

Orlando, the Venezuelan sleeping outside the church in El Paso, said he worked in Ciudad Juárez as a mechanic for a month. “It’s okay. The thing is the crime,” he says. “We have a lot of friends that have been kidnapped. They kidnapped them and asked money from their families.”

Title 42 exceptions

Several times weekly, COESPO receives calls from CBP, saying a certain number of migrants waiting in Ciudad Juárez can enter the country under a Title 42 exemption. Valenzuela says 75 migrants usually cross over the bridge at a time, but there is no hard or fast rule. The exemptions are supposed to be granted to families and those over age 70, migrants facing difficulties such illness or chronic conditions, or people who been victims of crime in Juárez.

COESPO asks the migrant shelters to select people who meet the requirements; the shelters themselves have sorted out a system for when its their turn to send guests.

A person working a Catholic migrant services group called the exemptions “discretionary” – both on the part of the CBP (how many would be admitted and how often) and the migrant shelter operators, who they say often use no clear criteria for selecting candidates. The person said of the selection process:

“There are no instructions for deciding who ‘yes,’ and who ‘no’. … The people in charge of the shelters are the ones making that decision. … We’ve also documented a series of abuses on the part of the some of those deciding.”

In January, the Biden administration unveiled the CBP One app, which it called an “online appointment portal to reduce overcrowding and wait times at US ports of entry” after Title 42 is lifted for non-citizens in waiting in Mexico and Central America. COESPO has started helping people enrol in the application, though reports from the border have focused on glitches in the app and some migrants having language issues.

Getting admitted

A Venezuelan family of three just admitted through a Title 42 exemption expressed relief after arriving in El Paso, saying they spent three months in Ciudad Juárez and had lost hope.

The family patriarch, 31, says their phone was robbed after a scary incident in San Pedro Tapanatepec, Oaxaca, where the INM had established a camp for migrants waiting to receive safe passage documents. He recalled hiding with his wife and young daughter in a hotel room after hearing from an employee that the CJNG drug cartel was supposedly on its way. He later had his phone stolen by force. He said:

“What we’re saying is that Venezuelans suffering mistreatment by the cartel are those who are receiving this exception to be able to apply for asylum.”

The family left Venezuela more than six years ago, relocating to Panama. The patriarch found work as a mechanic, which he described as “very well paid.” But he also spoke of “social decomposition” and “xenophobia” in Panama. After his daughter was born, he says, “We were already thinking about migrating.” He continued, “Over the past three months, you can look at the news from Panama. They’ve robbed three banks, a jewelry story and there’s a very large level of narcotics trafficking.”

Two other Venezuelans interviewed for this report also spoke of spending at least five years in Colombia, but deciding to move on. One person says their family suffered an extortion attempt. José, an engineer by training, decided to pursue better opportunities, explaining:

“The truth is Colombia treated me well. There was work. I always had work. My quality of life was average: food, housing … nothing luxurious, nothing extreme. … I’ve always wanted to get ahead and wanted a better quality of life. The United States always struck me as the best option.”

Orlando, one of the Venezuelans outside the Sacred Heart Church, was uncertain how he would resolve his immigration status in the United States. He wanted to work and was willing to do so in El Paso, but seemed to recognize the impossibility of his predicament:

“The governor of Texas is anti-migrant. There are other places like California, Colorado, Las Vegas. There are lots of places that receive migrants. That’s what we want: passage.”