Mexico celebrates La Virgen de Guadalupe

Millions descend on the Basílica de Guadalupe for the national patroness' feast day; AMLO beckons supporters in a show of force; and Mexican migration enforcement sets new record

Mexicans turned out en masse to celebrate the Dec. 12 feast of our Lady of Guadalupe, the national patroness, who Catholics believe appeared to an indigenous farmer, St. Juan Diego, in 1531 at Tepeyac Hill – site of the Basílica de Guadalupe, the world’s most visited Marian shrine. Pilgrims have returned in bigger numbers than ever after the site closed in 2020 due to the pandemic with the Mexico City government announcing 11 million visitors since Dec. 8.

It’s hard to overstate the importance of La Virgencita in Mexicans’ faith and sense of identity. Even non-Catholics often identify as guadalupanos. The country’s populist president also leveraged the virgin’s appeal by christening his political movement “MORENA” – Spanish for dark-skinned lady and a nickname for the patroness. He later announced his 2018 presidential run on Dec. 12, 2017 – Guadalupe’s feast day.

Three stories from 2016 and 2021 by this author attempt to explain the importance of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico and the current president’s attempts to leverage her popularity for political purposes:

More than a saint, Our Lady of Guadalupe represents Mexican identity

Our Lady of Guadalupe enthusiasm overpowers devotion to St. Juan Diego

Mexico’s president leverages Virgin of Guadalupe for political purposes

AMLO BECKONS THE MASSES INTO THE STREETS

Two weeks after civil society took to the streets to protest plans to overhaul the electoral system, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) beckoned his followers to central Mexico City for a counter-march and show of strength – in what was once his biggest bastion of support, the national capital, but a jurisdiction increasingly leaning toward the opposition.

The march coincided with the fourth anniversary of AMLO taking office – a date he has used for delivering “informes,” Mexican version of the state of union address, which the Mexican president insists on doing quarterly. It also followed AMLO’s penchant for perpetual campaigning, mobilizing his base and attempting to show widespread popularity – even has he maintains a relatively respectable approval rating of 59%. It’s a level little different from past presidents, spare his predecessor president Enrique Peña Nieto.

Duelling marches

The pro-AMLO march followed a Nov. 13 demonstration sponsored by civil society groups in support of the National Electoral Institute (INE) – and to oppose an AMLO proposal to replace the with an electoral agency easier for the executive branch to influence. (Last week’s newsletter covered the proposed electoral reform, a version of which is being pushed through congress.)

The contrasts between the marches – Nov. 13 and Nov. 27 – couldn’t be starker for observers, who noted López Obrador had lost his dominance of the street and needed to counteract any perceptions of slippage. Adrián Rueda, local politics columnist for the Excélsior newspaper, said the civil society march stiffened the spines of politicians who may have had their arms twisted by AMLO’s operatives and supported the original electoral reform. He also noted:

“(AMLO) wasn’t going to remain a defeated president and Andrés Manuel always doubles down: if you have a march, he’s going to have one with double the people. The difference is that he did it from the government and the other was done by civil society.

“The civil society march was to defend a cause and the (AMLO march) was organized with public money so people would applaud him.”

AMLO’s ‘acarreados’

The word “acarreado” has a long and unhappy use in Mexico’s political lexicon, referring to the people herded into political rallies and protests – often coercively under threat of losing their employment or social benefits, but also for inducements like a torta and a soft drink and maybe a few pesos. Several people who offer workshops to seniors through a Mexico City government program told the newspaper El Universal that they were required to force the beneficiaries to attend. One of the beneficiaries said she was promised help with a processing her request for a federal benefits card, along with a bagged lunch and 2,000 pesos (roughly $95.)

Buses clogged much of central Mexico City on the day of the march as AMLO supporters poured in from the provinces. Where the money for the trips came from remained a mystery, though no one doubted government or MORENA party support. The newspaper Reforma counted 1,787 buses used to transport people from the provinces and the outer reaches of Mexico City to the march. Stories also surfaced of government employees being forced to attending – including the National Guard, whose members were told to show up in civilian clothes.

Herding crowds to the Zócalo square in central Mexico City to fawn over the president drew comparisons to past decades of one-party rule under the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). Analysts pointed to another old practice from Mexico’s corporatist past being revived: “pasar la lista” – effectively: taking roll call, through which potential candidates, along with functionaries would show their organizing skills and loyalty to the president. Historian Ilán Semo of the Jesuit-run Iberoamerican University told this newsletter:

“One of the top loyalties in Mexico is bringing people to demonstrations. … (It) shows that a president is strong – above all, inside his party – and allows him to gauge who is performing and who isn’t. … (It’s) to show that he has more support than the political right in their demonstration (Nov. 13). But, above all, it’s loyalty in the ranks. This is key because the (presidential) succession race has started.”

MEXICAN MIGRATION ENFORCEMENT

Mexico set a record for migrant detentions in October, stopping 52,262 persons illegally in the country. The numbers surpassed the previous month’s total by approximately 10,000 detentions and nearly quadrupled the monthly average detained since 2013, according to an analysis by the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), a human rights think tank.

The record figures coincided with the U.S. government in October extending Title 42 to include Venezuelans, who had been arriving at the U.S. border in ever increasing numbers. Some 42% of the migrants detained in Mexico in October were Venezuelans, who have headed north in massive numbers after years of migrating to other parts of South America as their country collapsed under 21st Century Socialism.

Title 42 will be lifted Dec. 21, provoking concern from border patrol agents of a migrant surge, according to the Washington Examiner. WOLA, which advocates for more pro-migrant policies, partially concurred, but said in a March analysis, “Numbers would be likely to decline somewhat and stabilize as repeat crossing attempts reduce and the number of single adult apprehensions drops sharply.”

Migration though the Darién Gap – the thick jungle rife with bandits separating Panama and Colombia – continues unabated, despite the decision to extend Title 42 to include Venezuelans.

While migrants continue arriving in Mexican border towns, many have paused their journeys in the city of Monterrey, some 120 miles south of Laredo, Texas. The city of 5 million is perceived as safer than most Mexican border towns. Its booming economy is also underpinned by factories for export, offering plenty of employment opportunities, according to a Dallas Morning News feature, which described Monterrey as “a way station for migrants with eyes on Texas.”

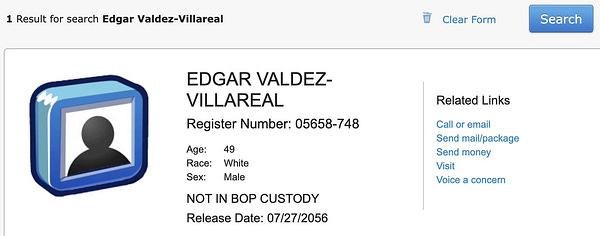

IMPRISONED NARCO ‘LA BARBIE’ DISAPPEARS

Fallen Mexican-American kingpin Edgar Valdez-Villarreal “La Barbie” is no longer listed as being in the custody of the U.S. Bureau of Prisons, despite being sentenced to 49 years in prison in 2018. Born in Laredo, Texas, and given the nickname “La Barbie” by a high school football coach for his good looks, “La Barbie” led a team of thugs known as “Los Negros,” which eventually operated as the armed-wing of the Beltán Leyva Cartel. He waged a bloody battle for control of the cartel’s territories stretching from the southern outskirts of Mexico City to Acapulco after Arturo Beltrán Leyva was killed by navy commandos in Cuernavaca in 2009. He was himself captured in 2010 without a shot being fired and extradited in 2015.

La Barbie, it was revealed, worked for the DEA and FBI, but continued smuggling drugs to the United States while cooperating, according to prosecutors. In an extensive write up on La Barbie and his mysterious disappearance from BOP custody, Borderland Beat noted:

“One of La Barbie’s most important contributions, according to the report, was passing along a tip that allowed Mexican marines to locate and kill his former boss, Arturo Beltrán Leyva, in 2009.”

Thickening the plot:

“La Barbie is expected to be a key cooperating witness in the trial of Genaro García Luna, Mexico’s former top security official from 2006 to 2012, who US authorities arrested in December 2019 on drug charges and taking millions in bribes from traffickers.”

In 2012, La Barbie sent a letter to investigative journalist Anabel Hernández, claiming to have rejected an agreement “with all the organized criminal groups” proposed by then-president Felipe Calderón. He said of García Luna, Calderón public security secretary, according to Spanish newspaper El País:

“I know for a fact that he has received money from me, from drug trafficking and organized crime.”

A spokesperson for García Luna at the time denied the accusations. García Luna goes on trial in New York next year on accusations he accepted bribes from the Sinaloa Cartel to allow it to operate with impunity.

García Luna podcast debuts

Investigative journalist Peniley Ramírez has been digging into García Luna’s dealings since late 2012, shortly before he moved to a $3 million house in Miami. “I started investigating how he got the money for that,” Ramírez said.

Ramírez wrote a book on García Luna and his deals. Her podcast will set the scene for the trial, tell the backstory on one of Mexico’s most controversial public functionaries of the past 20 years and offer a glimpse into Mexico’s sorry security situation and the alleged cartel infiltration into the upper echelons of government.

Writing in Reforma on Saturday, Ramírez said the podcast would explore García’s curious relationship with U.S. law enforcement, which long suspected misdeeds. Ramírez wrote:

“In the podcast, we expose the serious omissions of U.S. agencies – especially the DEA – in investigating García in the face of suspicions of corruption. We tell that, since 2001, García Luna’s teams stymied an operation to capture ‘El Chapo’ Guzmán and in 2006, when Felipe Calderón named him public security secretary, there were already at least four investigation in to possible links between García Luna and the Sinaloa Cartel.

“In addition to the president of Mexico, the U.S. government also trusted him. In the podcast we reveal how, since 2008, the U.S. embassy knew of complaints about the links between García Luna and narcotics traffickers. However, the day after leaving his post in Mexico, he moved to Miami. There he received payments of $60,000 monthly. Supposed, it was his salary as a consultant for a company that did not have an official address, telephone or website.”

NUEVO LAREDO CHAOS

A Dec. 7 clash between soldiers and presumed cartel gunmen claimed seven lives on the highway leading out of Nuevo Laredo toward Monterrey. That clash was preceded by firefights Nov. 28 after Mexican soldiers captured a Cartel del Noreste (CDN) leader, Heriberto Rodríguez Hernández, known as “El Negrolo.” SEDENA said in a statement that “El Negrolo” was implicated in the March abduction of Mexican soldiers and their families, “And the attack on military facilities and the U.S. consulate.” The U.S. consulate in Nuevo Laredo was hit with gunfire as violence erupted over the arrest of a cartel boss earlier this year. InSight crime said of El Negrolo:

“El Negrolo was the presumed leader of Tropa del Infierno (Hell Troop), the armed wing of the CDN.”

“Under his watch, Tropa del Infierno developed a reputation as a brutal fighting force. Starting in 2019, it has frequently clashed with the Jalisco Cartel New Generation (Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación – CJNG) and the Mexican Army.”

Nuevo Laredo remains a coveted cartel territory for the vast volume of international trade passing through what is the busiest commercial port of entry along the U.S.-Mexico border. CDN has an especially bloodthirsty reputation since emerging as a splinter group from Los Zetas – which itself originated as the armed wing of the Gulf Cartel comprised of former special forces soldiers. (InSight Crime published a useful map, breaking down the criminal landscape in Tamaulipas, which borders Texas.)

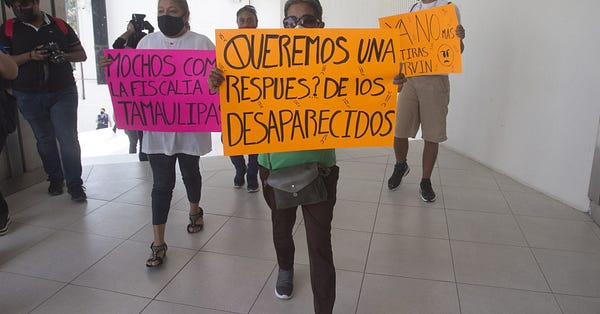

Disappearances on the highway of death

Mexico’s missing person crisis has mushroomed over the past 15 years – with disappearances in Nuevo Laredo and the highway connecting it with Monterrey being especially scandalous. Nuevo Laredo recorded 996 disappearances between Oct. 1,. 2016 and Feb. 8, 2022, according to Tamaulipas news organization Elefante Blanco.

Many of the disappearances occurred on the highway between Nuevo Laredo and Monterrey – a stretch chock-a-block with truck traffic – with 164 persons disappearing, mostly during the pandemic, according to Elefante Blanco.

ZACATECAS CHAOS

Over the past three weeks in the north-central state of Zacatecas, the local National Guard commander was killed during a raid; an attempt to break out presumed cartel associates let to a prison riot as a wave of narcobloqueos unfolded with tractor trailers and toll booths were torched; a federal judge was murdered outside his home; and bags of human remains were dumped out the entrance of a state university.

InSight Crime sums up the situation well – while noting some success on the part of federal forces in diminishing the homicide rate, which remains stubbornly high:

“Zacatecas is beset by Mexico’s two major rival cartels, the CJNG and the Sinaloa Cartel, as well as their regional allies. The groups have engaged in violent shootouts in rural areas like Jerez, close to poppy and marijuana cultivation areas, causing mass displacements.”

Dog carrying human head left by cartel captures horror of Mexico’s bloodletting

The horror of Zacatecas hit home in late October, when a video went viral on social media of a dog roaming the streets with a human head in its mouth. Police recovered the head in the municipality of Monte Escobedo, which media reported was left with a warning message from a criminal group.

The video set off a wave of subsequent stories from other states of dogs carrying human remains. In Irapuato, Guanajuato, a dog carrying a human leg led to the discovery of a mass grave containing 53 plastic garbage bags of human remains.

The discoveries reinforced perceptions of Mexico’s reality of out-of-control violence. Anthropologist Claudio Lomnitz sadly observed of the Guanajuato discovery:

“The crime was not discovered through an open investigation by the prosecutor’s office. A dog was responsible for the discovery, which was and is worth more than all the prosecutor’s offices.”

AMLO blames previous governments for Zacatecas problems

AMLO being AMLO blamed his usual suspects for the violence in Zacatecas: previous governments, while accusing his political opponents of ginning up the coverage for political advantage and downplaying the atrocities. He insisted that the judge, who was shot twice in the head, “has nothing to do with criminal activity.” He said: “It’s a complicated situation between these groups were allowed to grow and now we’re confronting them.”

#SEDENALEAKS: ARMY REFUSED TO CAPTURE EL CHAPO’S SONS

The #SedenaLeaks emails produced another example of cartel collusion: the army refused to detain two sons of now-imprisoned Sinaloa Cartel kingpin Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, despite receiving a tip from the DEA on their movements.

Sinaloa news organization Riodoce revealed the details of an exchange between a DEA agent and an army captain. The agent identified as Mathew A. Emerick wrote on March 16, 2016:

“We received information that the brothers Ivan and Joaquin GUZMAN-Salazar are going to travel to Mazatlan this week. It’s possible that tomorrow we are going to have information on the trip with numbers.”

The army captain responded that his superior said the “Chapitos” – as “El Chapo’s sons are known – were persons of interest, but that there was no arrest warrant. He also mentioned that with Mexico’s new criminal justice system – which was introduced between 2008 and 2016 and provides oral trials, a presumption of innocence and requirements for the proper presentation of evidence – “these kinds of persons go free when we present them” to judicial officials. The captain also said:

“These people are now unarmed or carrying low profile weapons to avoid being imprisoned. So we think we cannot act on this. And it’s better to wait for another opportunity when we can find more evidence.”

El Chapo’s sons, of course, mobilized their thugs and caused chaos in the Sinaloa capital Culiacán after one of them, Ovedio Guzmán, was arrested in October 2019. Ovedio Guzmán was released on the president’s orders after soldiers and their families were threatened.

THE LINGERING FALLOUT OF THE CIENFUEGOS FIASCO

The New York Times Magazine and ProPublica published a deep dive into the arrest and release of former Mexican defence secretary Gen. Salvador Cienefugos, whose case has caused a deterioration in cross-border security cooperation.

The article is long, but well worth reading or listening to, and spells out the origins of the investigation into Cienfuegos. The case started with a cop in Las Vegas, who “took a street case and built it into something very important. If the politics had gone a different way, he would have been a hero.”

But, ultimately, politics won out. Then-attorney general William Barr dealt with the blowback of a Mexican administration irate over the arrest – and likely facing an internal revolt from the military, which AMLO has depended so heavily on during his administration. Barr acted to preserve bilateral relations and security cooperation, having received assurances that Cienfuegos would be investigated in Mexico – a probe that barely looked into the accusations and quickly absolved the general. The Times-ProPublica report noted:

“The episode led to a near-collapse of law-enforcement cooperation between the two countries. Emboldened by what Mexicans saw as the D.E.A.’s humiliation, López Obrador accused the agency of “fabricating” its charges against the general. At the president’s behest, the Legislature imposed crippling new restrictions on U.S. agents’ ability to operate in Mexico. A Mexican police drug unit that worked with U.S. officials on sensitive cases was disbanded. For months, Mexico refused even to grant visas to dozens of D.E.A. agents assigned there.”

The attempt at holding a senior Mexican official accountable for alleged collusions with drug cartels proved impossible. As a veteran DEA agent ruefully said:

“If we had to pay a price in Mexico to finally prosecute someone like Cienfuegos, we were all willing to pay it because it would have made a difference. Instead, we paid the price and got nothing.”

MEXICO’S EVOLVING MARIJUANA MARKET

Marijuana production once provided much of Mexican drug cartel’s income – along with offering a cash crop for campesinos scratching out an existence in the country’s rugged mountain regions. That shifted somewhat in the 2010s after U.S. states started legalizing marijuana. Cartels moved more into other drugs, especially synthetic drugs like methamphetamine and later fentanyl, leaving campesinos devastated – especially as criminal groups in states such as Guerrero stopped buying opium poppies used to produce heroin and started focusing on flooding the U.S. with fentanyl.

InSight Crime has launched a four-part investigation into the shifts in Mexico’s marijuana market, which hasn’t entirely collapsed, but evolved to cater to increasing domestic demand. Legalization, meanwhile, is in the offing as the Supreme Court has decriminalized growing marijuana for personal consumption. (López Obrador has voiced his opposition to marijuana legalization – something analysts say has provoked foot dragging in congress, which the Supreme Court ordered to draw up regulations for legal consumption and the commercializing of cannabis.

In the introduction to its investigation, InSight Crime observed:

“Marijuana has become far less of a priority for law enforcement on both sides of the border. Today, authorities are increasingly focused on the trafficking of synthetic drugs, which are rapidly replacing plant-based drugs. Marijuana seizures in Mexico and at the US-Mexico border have steadily declined over the past decade, and the Mexican army is eradicating fewer marijuana plantations every year.”

EXTORTION SLIPS FURTHER OUT OF CONTROL

Mexican criminal groups have increasing moved into extortion, demanding protection payments from everyone from the most humble of small business owners across to avocado and lime growers and packers to the transportation industry. Statistics are notoriously dismal as most cases of extortion go unreported.

The Secretariado Ejecutivo del Sistema Nacional de Seguridad Pública (SESNSP), which collects crime statistics, reported only 8,828 cases of extortion in 2021. But INEGI, the state statistics service, estimates 4,910,206 cases of extortion in 2021 of which 246,138 cases ended up in a criminal complaint. Only 128,976 complaints resulted in an investigation being opened, according to Francisco Rivas, director of the anti-crime NGO National Citizen Observatory.

Writing in the newspaper El Universal, Rivas noted that extortion in 2020 had increased 18.72% over 2020. He wrote:

“It’s a crime where the rate of impunity is nearly 100%. That’s due to the absence of strategies (and) the lack of commitment on the part of many authorities; poor processes for receiving complaints; a poor institutional response; the absence of resources and little interest in providing the victims with access to justice.”

‘AN ANNOUNCED FAILURE’: MEXICO EXITS WORLD CUP EARLY

Mexico exited the World Cup without reaching the quarterfinals – again – the so-called “fifth match,” in which ‘El Tri’ (so named for its three-colour kit) hasn’t played since it hosted the tournament in 1986. The country usually bows out in the round of 16 in calamitous fashion – either badly underperforming (losing to upstart rival the United States in 2002), losing on penalty kicks (against Bulgaria in 1994), falling victim to a superhuman play (such as giving up “the goal of the tournament” against Argentina in 2006) or falling victim to the referee (as supposedly occurred against Holland in 2014, when a phantom penalty was called against Mexico.)

But Mexico failed to advance out of the first round for the first time since 1978 (though it missed the tournament in 1982 and was ineligible for 1990 for fielding overage players in a U-20 tournament.) Reuters summed up the situation with the savage headline: Mexico find way to end fifth-game course – not making the fourth.

Soccer as an explanation for modern Mexico’s shortcomings

Mexico’s soccer squad, its management and organization of the game has long explained many of the country’s worst vices – a topic long explored by the author of this newsletter.

From a 2015 story for Vice Sports on the firing of popular, but hot-headed coach Manuel Herrera, better known as “El Piojo,” The Louse:

“Some observers say the Mexican soccer system’s issues mirror many of the issues the country faces writ large: struggles with corruption, a lack of meritocracy, and culture in which the political and business classes prefer collusion to competition.

“Soccer in Mexico is less of a meritocracy than in other (countries) and hence it reflects the lack of professionalism that plagues the important positions in the country,” said Manuel Molano, adjunct-director of the Mexican Institute for Competitiveness. “Either playing, or training or managing the team, we cannot make sure that the best possible Mexicans are the ones in charge. Politics and some of our businesses work the same way.”

A 2013 story for the Christian Science Monitor, when Mexico struggled to qualify and lost to Central American minnows, noted:

“(Observers) cite Mexico’s soccer system as an example of some of the country’s most problematic practices – such as companies colluding or keeping competitors under control, instead of embracing competition – which limit player development in the domestic league and leave the national team ill-equipped for international tournaments.”

One-time coach Sven-Göran Eriksson, fired during a disastrous tenure prior to the 2010 World Cup, said of Mexico’s soccer overlords and their meddling in his autobiography:

“It was more or less the club owners that decided how the national team should be run, at least that's how things ran before I got there. It was important to make allies with the people high up in the football establishment, as if that would help the national team win games.”

Mexico’s domestic league is one of the wealthiest in the world. But observers point to poor business and sporting practices.

One practice is the rigging of the relegation system (in which one time descends to the second division and one team from the low league is promoted) so that the wealthy franchises would have to struggle for three-straight seasons to be demoted – something unlikely to occur. Another is the so-called “pacto de caballeros,” in which owners refuse to sign a player who departed for another league, unless he played for them prior to leaving Mexico. Both speak to the anti-competitive nature of Mexico’s economy, where monopolistic practices are rife.

Player underperformance and the self-criticism: Mexicans don’t work well in teams

Top Mexican players used to play domestically rather than test themselves in Europe’s top leagues. Analysts described it as being a big fish in a small pond: they earned handsomely at home and didn’t need to test themselves internationally. But Mexico started developing talent and winning at the junior level, claiming the U-17 World Cup in 2005 and 2011 and the Olympics (a U-23 tournament) in 2012. Mexicans often say they produce more top boxers than soccer starts because Mexicans supposedly don’t work well in teams.

One analyst, Eduardo García of business publication Sentido Común, attributed the success at the junior level to NAFTA opening the country and introducing a spirit of competition.

“The Mexican victories ... appear to be the beginning of the end of the theory that Mexicans, due to a deeply rooted cultural attachment to family and the individual ... don't know how to work as a team.”

Mexico subsequently stumbled through the 2010s with the golden generation in their prime – with some brief, but fleeting high points such as the performing strongly at times in the 2014 and 2018 World Cups, but exiting in the round of 16.

‘We played like never before, and lost like always’

A common refrain after the World Cup posits: “We played like never before, and lost like always.” Mexico’s World Cup futility provides plenty of fodder for professional and amateur psychologists and cultural observers.

Celebrated writer and columnist Juan Villero – recently the target of AMLO’s ire – comments often on the intersection of Mexican soccer and society. He wrote of Mexico prior to the World Cup in the newspaper Reforma:

“A country that defines itself by defeats, melancholy and solitude can well confront the national team’s failures, but its surprise wins with difficulty. What would truly be paralyzing for Mexicans would be to beat Argentina by a landslide. After that, what would we say? What would we do?” We would be facing a miracle and a phenomenon difficult to explain.”

Ricardo Trujillo Correa, an UNAM psychology, wrote of the inability to make the fabled fifth match:

“The main figure in Mexican football culture is the Mexican who doesn’t give up. That’s followed by symbolic vindication in the face of an eternal confrontation with a powerful team and, finally, dignity: ‘It was very difficult match, but we gave 100 percent and we have to keep working.’ ”

MEXICO PLAYS FOR TIME ON TRADE DISPUTES

Mexico has increasingly taken a hard-line on trade disputes with the United States – something noticed by The Wall Street Journal editorial board, which said of the Mexican economy secretary’s recent visit to Washington:

“If Mr. López Obrador thinks he can honor the parts of the USMCA he likes but disregard what is inconvenient, the Biden Administration has no reason to delay arbitration and a likely ruling against Mexico.”

The United States and Canada filed complaints under the USMCA over the summer alleging the Mexican government was undermining U.S. and Canadian energy investments – mostly in renewable energy – by favouring the state-run Federal Electricity Commission.

The USMCA allows for dispute resolution settlements of 75 days, which can be extended – and have been extended to reach 130 days, the Journal noted.

The Journal accused the AMLO administration of “slow-walking” trade talks – a perception common in Mexico as AMLO changed economy secretaries in October. He replaced Tatiana Clouthier, his 2018 campaign manager and perhaps the last pro-business voice in his government, with Raquel Buenrostro, who gained a fearsome reputation as head of Mexico’s tax agency by putting screws to big companies with outstanding tax disputes. (In introducing Buenrostro, AMLO lauded her work at the tax agency, because tax revenues increased in 2020, despite the economy shrinking more than 8% and no new taxes being introduced.)

Buenrostro immediate sacked the team responsible for international commerce, which included people with experience negotiating the original NAFTA agreement in the early 1990s. She replaced them with inexperienced loyalists, prompting a source familiar with the inner workings of the economy secretariat to observe:

“They’re going to run out the clock on the sexenio and pass it on to the next president.”

Corn dispute simmering

In the meantime, Mexico and the United States are headed for another trade dispute – this time over GMO corn, which AMLO has promised to ban by 2024. AMLO previously signed a previous decree, banning imports of GMO corn by 2024. In November, he signed another decree banning the use of glyphosate.

The issue has so alarmed U.S. officials that the both Iowa senators sent a letter to President Joe Biden urging intervention and predicting losses of more then $3.5 billion in the first year a ban takes effect. U.S. Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack travelled to Mexico City to urge AMLO to reconsider his corn policies.

AMLO responded with his usual verbosity, speaking of corn being the country’s cultural heritage and mentioning a letter from Oaxaca painter Alejandro Toledo on the issue, “telling me, ‘don’t allow this; no to GMOs, no to GMO corn.’ So … and there’s the issue of health.” He continued with the proposal:

“We going to have the health agency of the United States and Cofepris (its Mexican counterpart) study this. And this is good not only for Mexican consumer, but also U.S. consumers.”

Mexico imports more U.S. corn than any other country – most of it yellow corn for animal forage.

‘Pro-business’ voice exits AMLO’s cabinet

In early October, then-economy secretary Tatiana Clouthier read her resignation letter at AMLO’s morning press conference. She spoke of burnout – and a source, who’s friends with her, confirmed there was a family situation. Clouthier, who served as AMLO’s 2018 campaign manager, then turn to embrace the president in what became the most visible manifestation of AMLO’s approach to politics and management: turning the could shoulder to those falling out of favour, along with public humiliation.

Analysts described her as the last pro-business voice in the AMLO administration, having links to the business community in her native Monterrey (though Clouthier clan is originally from Sinaloa.) Clouthier served as AMLO’s campaign manager, but analysts describe her role as being more of a surrogate. She memorably compared the rise of AMLO to that of president Obama, telling the PBS Newshour:

“I believe that it would be a situation similar to the one you lived in the United States the moment that Barack Obama was elected, in the sense that people were able to open their ears and open their eyes to see the world differently.”

More importantly, she worked to convince middle-class Mexicans and and northerners suspicious of leftists to vote for a southerner and populist like AMLO – in a country where norteños traditionally won’t support candidates from the less-economically developed south. As the daughter of 1988 PAN presidential candidate Manuel Clouthier – a barnstormer, who died in a mysterious car crash the next year – Clouthier put conservative panistas’ goodwill for her family toward AMLO’s campaign.

Monterrey political analyst Bárbara González told the FT of Clouthier’s importance:

“Her role was that of a spokesperson who could speak to soft sympathisers. She was a guarantee that they would fit into [López Obrador’s] project.”

Failed counterweight to MORENA ‘radicals’

People close to Clouthier say she disagreed strongly with AMLO’s move to put more power in the hands of the military – a topic discussed regularly in this newsletter. Her own brother speculated as much via Twitter.

But her departure showed the failure of moderates in AMLO’s MORENA coalition – a big tent, which includes two former PAN presidents, evangelicals and hard-left radicals – to influence the president. Clouthier arrived in AMLO’s campaign through Monterrey businessman Alfonso “Poncho” Romo, a maverick who married into one of the city’s best-known industrial clans and came to support AMLO in the early 2010s. Romo served as AMLO’s chief of staff, but departed in late 2020. Clouthier subsequently followed.

A source close to Romo recalled the business telling him that he and Clouthier would act as “counterweights” – to which the source responded:

“The radicals around Andrés Manuel have 20 years with him. You only have four years with him or five years. You’re not going to influence him.”

Three amigos summit – with AMLO floating ‘integration’ ideas

AMLO announced another version of the North American leaders summit for Jan. 8 and 9 in Mexico City. The summit comes as relations deteriorate. There are the trade disputes, which included Canada, joining the U.S. complaint on energy investments. Security cooperation isn’t especially close and AMLO seems bugged by USAID funding for non-governmental groups he considers political opponents.

The president again raised talk of “sovereignty,” along with his fanciful idea of continental integration – a modern-day Simón Bolivar, who fruitlessly pursued the integration of South America only to conclude: “All who served the revolution have plowed the sea.” He said at a morning presser:

“I do want to discuss the integration of America because it has been shown that economic integration helps us with respect for our sovereignties”.

Axios reported Dec. 6 that Biden is expected to agree to the summit, but no word yet from the Canadian prime minister.

AMLO muses from time to time about making the Americans into something akin to the European Union. But it’s a non-starter in much of the region, which is in competition with each other as much as cooperating. AMLO also reacts vociferously at any suggestions of “intervention” from other countries – especially the United States. But some in the United States noticed his comments – and reacted accordingly.

U.S. climate focus

The U.S. seems especially focused on pushing AMLO to take action on climate change – a topic he seldom addresses as he pursues projects such as building a new refinery in Tabasco (and buying one in Deer Park, Texas), along with reactivating coal-fired plants on the Texas border and passing laws prioritizing power produced but he state-run CFE (often from fossil fuel sources) over privately produced renewables.

Mexico agreed to reduce its carbon emissions 35% by 2030, an increase from its previous commitment of 22%.

To make it happen, Mexico has promised to spend $48 on climate change projects in Mexico – with help from the United States – and for Mexico to somehow achieve a 50% share electric vehicle sales by 2030. Mexico intends to ramp up the production of renewables, even as López Obrador puts a priority on fossil fuels produced and consumed under management of state-run companies.

Pemex has also pledged to invest $2 billion to stop flaring and venting across its oil and gas operations. Mexico ranks among the world’s top 10 countries for flaring, according to the World Bank – and among only three countries in the cohort with increased flaring over the past decade. The bank noted in its 2022 Global Gas Flaring Tracker Report:

“Despite oil production declining over the last 10 years, Mexico has increased flaring by over 50 percent, with a sharp uptick since 2018, rising from 3.8 bcm to 6.5 bcm in 2021. This increase suggests oil production is occurring at wells with higher gas- to-oil ratios and, with no outlet for the gas, the additional gas produced is flared.

“Mexico’s focus over the last few years has been on energy security, however the increase in gas flaring has occurred while Mexico has also steadily increased natural gas imports, highlighting the potential flare gas recovery could play in its energy independence.”