'The best investment of the cartel'. US court convicts Mexico's former anti-crime boss of taking cartel bribes

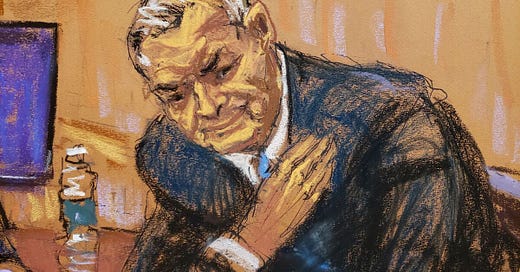

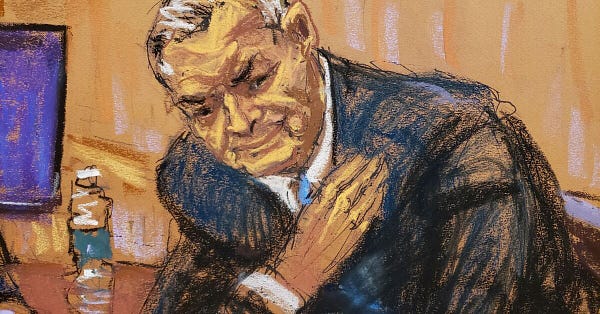

Genaro García Luna was once celebrated as the architect of Mexico's security strategy and the Federal Police. But a New York jury found him guilty of protecting the Sinaloa Cartel.

A New York jury convicted Genaro García Luna on accusations he took bribes from the country’s drug cartels, marking a stunning downfall for the architect of Mexico’s crackdown on criminal gangs and a public figure previously considered so powerful he was commonly called “The Mexican Hoover.”

Federal prosecutors alleged García Luna collected illicit payments from the Sinaloa Cartel while serving as public security secretary between 2006 and 2012, when he oversaw the creation of the Federal Police and enjoyed the full confidence of then-President Felipe Calderón. (He allegedly also collected bribes while head of the Federal Investigative Police – AFI – in the early 2000s.)

The collusion went so far that prosecutors accused him of allowing cartel thugs to use police uniforms and equipment, and the Mexico City airport – under Federal Police protection – was turned into way station for cocaine transiting Mexico to the United States.

García Luna faces a minimum sentence of 20 years in federal prison. His charges included conspiracy to smuggle cocaine into the United States and lying on his U.S citizenship application. He will be sentenced June 27. Prosecutors said in a statement after the Feb. 21 conviction:

The defendant used his official positions to assist the violent Sinaloa drug cartel in exchange for millions of dollars in bribes. Garcia Luna’s conduct included facilitating the safe passage for the Cartel’s drug shipments, providing sensitive law enforcement information about investigations into the Cartel, and helping the Cartel attack rival drug cartels, thereby facilitating the importation of multi‑ton quantities of cocaine and other drugs into the United States.

The case reverberated in Mexico, where President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) sniped regularly on the trial from the pulpit of his morning press conference – revelling in the opportunity to embarrass Calderón, his most hated political opponent and the man who narrowly defeated him in the 2006 election.

His communications squad, meanwhile, posted updates from the trial to government social media – with his spokesman snarkily tweeting after the trial: “Justice has been done for the person who was Felipe Calderón’s squire. The crimes against our people will never be forgotten.”

AMLO, who has shown solicitousness toward the Sinaloa Cartel throughout his presidency, quixotically suggested García Luna address the court “for the good of the country” and reveal “if he received orders or informed ex-presidents” Vicente Fox and Felipe Calderón. The president also called on Calderón, using the less polite form of you – “tu” – rather than the more formal “usted” to answer “why you named García Luna and if you knew or didn’t know.”

Calderón’s crime-fighting legacy tarnished

Calderón won office in a close 2006 election, which AMLO considered rigged and never conceded – and continues to relitigate to this day. He staked his presidency on bringing drug cartels to heel, sending soldiers into his home state of Michoacán shortly after taking office and following La Familia Michoacana announcing its arrival by bowling the severed heads of rivals onto a dance floor in the avocado-growing hub of Uruapan.

Calderón vehemently denied knowing anything about García Luna’s dealings with drug cartels, saying he never distinguished between criminal groups, “never negotiated with criminals,” and that he “combatted all those who threatened Mexico, including, of course, the so-called Cártel del Pacífico” (better known as the Sinaloa Cartel.)

Calderón also insisted, “The fight for Mexicans’ security was not the responsibility of one person.” The statement alluded to perceptions of García Luna running his own fiefdom in the SSP – where he oversaw the building the Federal Police – but also claims that he had the president’s ear and unwavering support.

Guillermo Valdez, former head of CISEN (Mexican intelligence) under Calderón wrote in the magazine Letras Libres of García Luna’s authority:

“The first myth is that García Luna was president Calderón’s strongman and the government’s master security strategist. … “The security strategy was a collective effort in the security cabinet and President Calderón decided. Most of the operations in the states were carried out by the army … and it was impossible that the (public) security security had any ability to influence the deployment of troops and how they operated.”

A gift for AMLO

Attempts to downplay García Luna’s role in Calderón’s security crackdown and suggestions from political contemporaries that the trial served up scant evidence of collusions (see further down) failed to diminish the fallout for the former president and his National Action Party (PAN).

Calderón had recently presented a proposal for united the anti-AMLO political forces ahead of the 2024 presidential elections. But his legacy and role in Mexican public life – and that of his wife and 2018 presidential aspirant, Margarita Zavala, along with the PAN (which Calderón official abandoned) – suffered a severe blow with the García Luna conviction.

Writing in the newspaper Reforma, Jorge Volpe – a sharp critic of Calderón and his security crackdown – noted AMLO has followed the pattern of investing authority for security in a single institution: the National Defence Secretariat (whereas Calderón bet on the SSP). Volpe said of the former president:

“GL’s conviction represents, at least, the end of Calderón’s political life, along with that his inner circle. And, in good measure, the PAN.

“López Obrador has celebrated the conviction as a personal triumph and will capitalize on it so that his preferred candidate wins in 2024. What occurred with GL confirms his idea of the mafia in power: the diagnosis of his predecessors was always correct.”

AMLO has never shied from accusing his political opponents of having the same moral stature as narcos – playing on perceptions that corrupt politicians do more damage than drug cartels. Writing in the newspaper El Financiero, columnist Enrique Quintana posited that AMLO “won the narrative” with the García Luna conviction, saying, “Those who now question his government can be compared in the presidential narrative to García Luna.”

Already, AMLO took to comparing protesters marching to defend Mexican democracy on Sunday to García Luna – with his supporters spreading the hashtag #MarchadelosNarcos.

Troubling questions

The case raised troubling questions in Mexico, where investigations against figures such as García Luna are seldom pursued and justice is carried out in the United States – if at all.

AMLO’s interest in García Luna facing U.S. justice contrasted sharply with his intervention in the case of former defence secretary Gen. Salvador Cienfuegos, who was detained in the United States in late 2019 on accusations of protecting drug cartels.

The Mexican government – under pressure from the military, who AMLO has leaned on heavily throughout his administration – lobbied US officials to drop the charges against Cienfuegos, which they did, arguing it was in the national interest and Mexico would investigate the general. Mexican investigators promptly cleared Cienfuegos, but the federal prosecutor’s office has belatedly started building case against García Luna and plans to pursue his extradition.

End of an era of cooperation?

Journalist Tim Golden published a deep dive on the Cienfuegos fiasco for ProPublica in December, which showed similar doubts if prosecutors could prove the case beyond a reasonable doubt. With Cienfuegos sent back to Mexico and the García Luna case resolved, how much further U.S. officials go in pursuing big-time cases of Mexican corruption and drug trafficking remains uncertain. Golden wrote:

The Eastern District is pressing ahead with the case against García Luna, who is scheduled for trial in January. But the broader effort that agents and prosecutors imagined — to take on Mexican drug corruption wherever it might reach — now seems impossibly remote. Biden officials insist that they are still trying to tackle the drug problem. But if they want to get anything done with the Mexican government, they say, they need to avoid confrontation.

Security analyst and former intelligence official Alejandro Hope also described the conclusion of the García Luna case as “the end of an era.” Rather than another “trial of the century” being in the offing, Hope noted in his El Universal column that the García Luna conviction “doesn’t open another cycle of spectacular trials. The conditions that allowed a trial like this no longer exists.”

He pointed to a drastic reduction in extraditions from Mexico to the United States: 54 people extradited in 2022, a 53% reduction from a decade earlier.

In the future, he said, big suspects would be wary of heading to the United States, where García Luna was arrested and Cienfuegos went with his family for a vacation at the time of his capture. In cases such as that of Ovidio Guzmán – El Chapo’s son who was captured last year in Culiacán – “nobody from the current government will put much effort into extraditing (him). At a minimum, they’re going to everything possible to set back the process.”

He also pointed to the lack of cooperation between the United States and Mexico under the AMLO administration, saying:

These kinds of cases often require contacts and trust between members of the security apparatus in Mexico to complement the investigations or confirm some hypotheses. The contacts are surely still there, but trust has most likely deteriorated after the Cienfuegos fiasco and the García Luna trial. It’s hard to know how much, but it is difficult to assume that there is not some resentment within the security apparatus after these cases.”

Beyond a reasonable doubt?

García Luna’s lawyers and some analysts in Mexico – including some who served in the Calderón administration – described the trial as underwhelming and leaning exclusively on the explosive testimony of convicted narcos. As Insight Crime noted in a post-trial commentary:

The abundance of sensational testimony contrasted with the relative lack of hard evidence supporting the US prosecutors’ contentions about García Luna’s alleged criminal activities. García Luna’s lawyer Cesar de Castro emphasized this point throughout the trial, arguing that there was "no money, no photos, no video, no texts, no emails, no recordings, no documents -- no credible, believable evidence,” upon which to convict García Luna.

Court observers also questioned the prosecution’s case. New York Times reporters Alan Fleur and Nate Schweber wrote when the case was about to go to the jury:

“Even during the jury selection process, the prosecutors in the García Luna case made clear that they were not going to introduce reams of intercepted text messages or hours of recorded conversations of the sort that were used against top cartel defendants like Joaquín Guzmán Loera, the drug lord known as El Chapo, who was convicted on all charges in the same Brooklyn courthouse in 2019.

“The García Luna case, as they explained, was ‘a cooperator case’ and would rely on stories about the defendant told in person from the witness stand.”

Explosive testimony included Sergio Villarreal Barragán – nicknamed “El Grande” due to his massive stature – insisting that García Luna was already being paid while leading the AFI. Villarreal, a lieutenant with the Beltrán Leyva Cartel – a criminal organization aligned with the Sinaloa Cartel at the time – claimed García Luna got a cut of any drug shipments “stolen from rival cartels,” according to Borderland Beat.

He testified of a deal in a warehouse with a load stolen from the Gulf Cartel, which Borderland Beat said:

“For this load, the corrupt cops’ share was worth $14-16 million. ‘It was a good amount,’ stated El Grande. The cash was handed over in cardboard boxes.”

Jesús Zambada García, identified by the New York Times as the brother of El Chapo’s longtime business partner Ismael Zambada García, testified that he delivered $2 million in duffle bags to García Luna at a restaurant in Mexico City’s posh Polanco district. It was a repeat of an accusation he made in his testimony in El Chapo’s trial.

The New York Times said of the testimony of Israel Ávila, a Sinaloa cartel accountant, on the turbulent relationship between García Luna and Arturo Beltrán Leyva (leader of the Beltrán Leyva Cartel until killed by navy marines in 2009):

“Mr. Ávila told the jury that when the cartel erupted into a civil war, Mr. Beltrán Leyva wanted to know whether Mr. García Luna would support his side or the side of his top rival, (El Chapo). … When Mr. García Luna failed to provide an answer, Mr. Ávila said, Mr. Beltrán Leyva had him kidnapped.

“The abduction lasted a week, other witnesses have said, and ended without harm to Mr. García Luna.”

AMLO threatens legal action

Jesús “El Rey” Lambada, brother of Sinaloa Cartel leader Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada (considered an equal of El Chapo in a cartel that functions as a confederation) testified that Federal Police under García Luna provided easy passage for contraband flowing through Mexico’s ports and the Mexico City airport. Keegan Hamilton, whose reporting on El Chapo’s trial and later García Luna’s trial proved indispensable, wrote in Vice News:

“When El Chapo broke out of prison in 2001, El Rey arranged to have him picked up in a helicopter and driven into the Mexican capital with a police escort for safekeeping. “

But El Rey’s testimony generated enormous interest after García Luna’s lawyer probed previous comments from El Rey to U.S. investigators “about paying Andres Manuel López Obrador $7 million.” Hamilton continued:

“Rey initially said he did not recall such a payment, but when Cesar de Castro (the lawyer) reviewed his notes and asked about another person – a prominent lawyer and former government official in Mexico City. … Rey replied: ‘I do remember paying him some money, that according to him, was for the campaign, but not [for] paying López Obrador.’”

During a sidebar requested by the prosecution, Hamilton reported, the government didn’t dispute Rey made the comment, but argued it created a “sideshow.” “We’re talking about a sitting president,” the prosecutor said, according to the transcript, “and this witness has family in Mexico.” The judge agreed with the prosecution.

For his part, AMLO promised to sue García Luna’s lawyer for defamation.

MEXICO MARCHES FOR DEMOCRACY

Mexicans marched en mass in repudiation of AMLO’s attack on the National Electoral Institute (INE), which undermines its ability to convene elections and threatens the country’s young democracy. More than 100,000 protesters dressed in pink and white (the INE colours) poured into the central Zócalo square, where AMLO has beckoned his followers over the past 20 years for protests.

Tens of thousands more marched through city centres and town plazas across the country in one of the largest anti-AMLO protests since he took power in December 2018 (surpassed only by the burgeoning feminist movement, who during the early years of AMLO’s administration were his most indefatigable opponent and a group he unsuccessfully tried to belittle as “conservatives”.)

AMLO predictably derided the protesters a “conservatives,” though he failed to address an old statement in which he said he would resign and retire to his ranch in Chiapas if 100,000 Mexicans mobilized against him.

INE budget cut by a third

The protests followed Congress approving the so-called “Plan B,” which slashed the $760 million INE budget by a third, leaving it hamstrung as it prepares for the 2024 elections (in which AMLO is constitutionally prohibited from seeking re-election, but is pushing for his MORENA party to retain power and continue his so-called “fourth transformation.”)

Some 6,000 employees from the INE’s 17,000 strong workforce would also be released, according to The Wall Street Journal – including many who issue voter identifications (necessary to vote and the nation’s preferred form of ID), workers training volunteer poll clerks and the staff maintaining the voter list.

AMLO has long blasted the INE as bloated and portrayed its functionaries as overpaid. INE was founded after the scandalous 1988 election, when a mysterious computer crash in the interior ministry wiped out early elections results favouring the left. (The then-interior minister Manuel Bartlett is now part AMLO’s inner circle.) The Federal Electoral Institute (IFE) was subsequently founded as an autonomous institution to oversee elections.

“The Federal Electoral Institute had recovering trust in elections as its mission,” José Woldenberg, the IFE president who oversaw the end of one-party rule in 2000, told this newsletter.

Expensive, but necessary

Part of the reason for the high price of the IFE (which became the INE after an electoral reform in 2014) was that the institute was started from scratch. The ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) was also fond of subterfuge and parts of it were dragged along unwillingly toward democracy.

“The electors’ list was started from scratch. The 1988 electors’ list was thrown in the garbage. That’s not a metaphor; it was thrown in the garbage,” Woldenberg said.

Hiring a large bureaucracy was necessary, according to Woldenberg, because previously electoral employees were either temporary or linked to a political party – making it necessary to have career civil servants.

International attention

The pro-INE marches came as international attention turns toward AMLO’s increasingly authoritarian regime, which largely gone unscrutinized as analysts, journalists and editors reacted to the bombast of Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro – while seeing AMLO as something of a bore: a folkloric populist with eccentric ideas and prone to batty and soliloquies.

Several of the most prominent commentators on threats to global democracy visited Mexico in recent weeks, including David Frum, Anne Applebaum and Giddeon Raichman of the Financial Times – even though analysts, including the author of this newsletter, have warned of AMLO’s looming attempts to undermine the electoral authority (but found scant interest from international editors focusing on Trump, Bolsonaro and others.)

The middle class marches

The protests turned out members of Mexico’s middle class, according to press reports – usually people with university educations, who AMLO has derided as “aspirational” (unlike the poor and the “pueblo” he claims to represent.) The middle classes voted for AMLO in the 2018 elections, but rebuked him in the 2021 midterms – especially in Mexico City, where half the boroughs opted for the opposition in what had been an AMLO stronghold for 20 years. Multiple voters told the author of this newsletter that the president “wants to do away with the middle class,” though they expressed dissatisfaction with the opposition, too.

Political science professor Federico Estévez described the dynamic in the capital as “cosmopolitans versus populists.”

TELSA INVESTS IN MEXICO – IN SPITE OF AMLO

Tesla will build in a massive truck plant in the northern state of Nuevo León, ending months of speculation, along with a competition between states to land the investment, and AMLO’s attempts push the electric automaker toward his electoral heartland in central and southern Mexico.

AMLO revealed at his Feb. 28 press conference that Tesla would invest in Monterrey, in spite of attempts by the president to strong-arm the company into investing elsewhere – arguing Monterrey lacked sufficient water. The announcement followed a conversation between AMLO and Tesla founder Elon Musk on Feb. 27.

“There’s now an understanding. They’re going to invest in Mexico and put the plant in Monterrey with a series of commitments to confront the problem of water shortages,” AMLO said in his morning press conference. “He was very receptive, understanding our concerns and accepting our proposals, which be known tomorrow. This is going to mean a considerable investment and many jobs.”

The investment marked a massive win for the Mexican economy, which has attracted all of the major automakers over the past three decades – drawn by low wages, skilled workers and proximity to the U.S. market. It also marked an advance for Mexico in electric vehicle manufacturing and follows an announcement from GM to convert its massive plant in Saltillo into an EV facility.

AMLO couldn’t strong-arm Musk?

Speculation over Tesla’s designs on Mexico started with a Musk visit in Monterrey in October. Details followed, including supposed plans for building a plant in suburban Santa Catarina.

Stories then surfaced in the media that the federal government wanted Tesla to invest elsewhere in Mexico. Reforma ran a front-page story on Tesla being urged to invest to the north of Mexico City in Mexico State – site of an industrial park near the new Felipe Ángeles International Airport (AIFA).

“Tesla is looking at investing in that area to take advantage of AIFA, since the site could serve as a base for the company to export from there via air,” AMLO’s spokesman Jesús Ramirez Cuevas told Reuters.

The airport stands as one of AMLO’s prestige projects – part of his vision of state-sponsored mega-projects propelling development – but has attracted few flights and passengers. But politicians from his MORENA party in Mexico State – the country’s most populous and site of elections this spring – were quick to link the possible investment with the underused airport.

No electricity in Monterrey?

At one point, Tesla was urged to invest in other parts of Mexico due to a lack of electricity in Monterrey, according to sources speaking with the newspaper Reforma.

The Federal Electricity Commission (CFE) apparently couldn’t supply the required energy for the new new factory – the product of AMLO’s policy of forcing firms to purchase from the CFE and not permitting them to build self-generation plants. (The environment ministry denied Audi permission to build a solar park for its plant in Puebla in 2022, arguing it was only for the company and not for local use.)

No water in Monterrey?

Monterrey suffered a severe drought in 2022, with reservoirs evaporating, taps running dry and people being forced to cue with buckets as tanker trucks delivered scarce water. Industry, however, continued uninterrupted – the product of companies holding permits for wells which they’ve had for decades.

AMLO spent much of February insisting that Tesla search for a location in the south of Mexico – an area, which resembles Central America (while northern Mexico resembles the southern United States) as the prosperity of NAFTA largely passed the region by. A native of Tabasco – where the state-run oil industry underpins the economy – AMLO has pledged to promote economic development in the south, starting with a pair of railways and a behemoth refinery.

Some 70% of Mexico’s water is in the south of the country – a fact AMLO repeats often, when talking of industries such as brewing, which he wants to stop in the dry northern borderlands. Some analysts saw water as an excuse for sending investment to his preferred destinations – pointing to Constellation Brands, which was building a brewery in Mexicali until AMLO called a snap referendum. The company was forced to cease construction, but ultimately agreed to move to Veracruz – a move done with incentives, according to a source.

“It’s that we want to order growth,” AMLO said at one point in explaining why he wanted Telsa to operate outside Monterrey.

Electoral politics?

With AMLO pushing Tesla to invest outside of Monterrey, various state governments made pitches – though many lacked seriousness. States can offer incentives such as land grants, breaks on their property taxes and permitting help (enticements given with past automakers.)

Nuevo León ultimately got Tesla – with Musk not wavering much from the company’s original plan. But analysts wondered aloud what made AMLO give. Bárbara González, a political analyst in Monterrey, asked “what (AMLO) got in exchange for not placing any more obstacles?”

MORENA ran fourth in the 2021 Nuevo León elections. Gov. Samuel García won with the Movimiento Ciudadano party, which has not joined the PRI, PAN and PRD in an anti-AMLO alliance. González speculated García may have given AMLO assurances he or his party would run solo in 2024 – splitting the opposition and providing MORENA a clearer path to retaining the presidency.