Why Mexico's president and her predecessor have an 'aura of honesty'

Mexico sinks five points in the annual Corruption Perceptions Index, but Sheinbaum and AMLO escape all scandals

A version of this article appeared in The Mexico Brief.

Andrés Manuel López Obrador swept to office in 2018 on an anti-corruption agenda. He followed the now-detested former president Enrique Peña Nieto, whose government became associated with graft. AMLO cited the annual Corruption Perceptions Index from Transparency International as proof of Mexico’s slide in decadence under his predecessors. AMLO said in his 2018 inaugural address:

“According to the latest measure by Transparency International, we occupy 135th place compared to 176 countries evaluated and we moved to that place after being in 59th place in 2000, rising to 70th in 2006, climbing to 106th in 2012 and reaching the shameful position in which we find ourselves in 2017.”

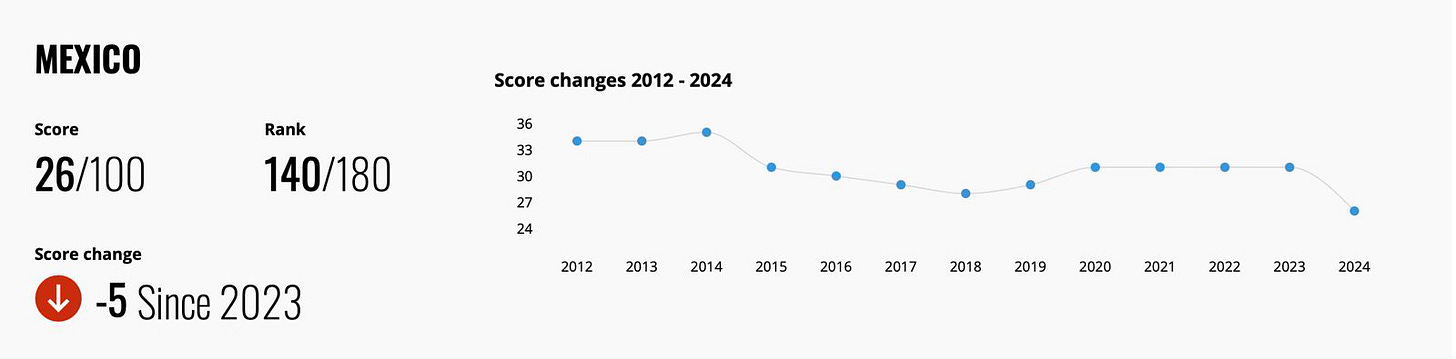

Mexico remained mired in low ratings in the TI survey through the first five years of AMLO’s administration, moving up slightly from a score of 29/100 in 2019 to 31/100 in 2023. Then it tumbled to just 26/100 in 2024, according to the latest edition of the TI survey. Mexico ranked 140 of the 180 countries measured by TI this year, lagging behind Peru, Bolivia and El Salvador, while barely beating Guatemala, Paraguay and Honduras.

The 4T – as AMLO christened his political movement – often seeks external validation such as opinion polls showing Claudia Sheinbaum and her predecessor among the world’s most popular leaders. But the current president showed predictable scorn for the latest edition of the Corruption Perceptions Index.

“Fortunately, people’s perception is different,” she said at her morning press conference. She then pointed to increased tax revenue – without raising taxes or approving a fiscal reform – as proof. “Privileges ended, corruption ended,” she added. “So obviously what there is is a change of regime, from a regime of corruption and privileges to a regime of honesty.”

78 per cent approval rating

It’s hard to argue with the first part of her retort: Sheinbaum won power with more than 60 per cent of the vote after running on an agenda of continuity. The latest El Financiero poll put her approval rating at 78 per cent. The annual Latinobarómetro poll of Latin American attitudes showed Mexican satisfaction with democracy hitting its highest level since the survey’s start in 1995.

AMLO spoke ad nauseam of “morals” and boasted of his own “moral authority.” Sheinbaum has branded her government with the gloss of “honesty.”

Much of AMLO’s claims seemingly came from the idea that his mere presence in the presidency would change the country. “We’re going to clean corruption out of government from top to bottom, like cleaning the stairs,” he once famously said.

AMLO’s words carried weight with the population. He pushed a narrative that the money for social programs was “recovered” from thieving politicians – something that stuck in the minds of recipients, who came to see him as something of a Robin Hood figure.

Presidential pleas of poverty

The former president also made periodic pleas of poverty, in which he showed an empty wallet – spare the odd bill – and claimed not to have any assets other than a property in Chiapas. He wore rumpled suits, flew coach on VivaAerobus (Mexico’s version of Spirit Airlines, though he later took military planes) and was never spotted in the fancy restaurants frequented by Mexico's political class.

“It gives him an aura of honesty as the man who doesn’t need anything,” Ilán Semo, historian at the Iberoamerican University in Mexico City, told the Washington Post.

Mexican DOGE

AMLO’s personal parsimony extended into government. He preached fiscal austerity – sometimes called, “Franciscan Poverty – in which he carried out a Mexican version of DOGE. He slashed bureaucracy and cut spending on everything from scientific research to health spending to software licenses for government computers. Bureaucrats were even banned from charging their smart phones at work, while heating and cooling were prohibited in some offices.

Former collaborator described it as traditional thinking on the Mexican left: government spends wastefully. It also allowed AMLO to be seen applying austerity “in the logic of non-corruption.”

Yet for his talk of combating corruption, AMLO preferred anti-corruption politics to actually taking action. He cancelled construction on the partially completed new Mexico City airport upon taking office in 2018, alleging – you guessed it – corruption in the project. (Passengers at the dilapidated Mexico City International Airport, which was to be replaced by the cancelled project, pay a user fee to reimburse bond holders for a project that will never be built). The Financial Intelligence Unit, which is ostensibly tasked with tracking the illegal money floating criminal groups, routinely pursued political opponents and critical journalists. Carlos Bravo Regidor, a political analyst, told The Globe and Mail in 2021”

“AMLO doesn’t have an anti-corruption policy, [but] he’s very good at anti-corruption politics. His idea is not to fight corruption, but to use corruption to his advantage, even if he is personally not as corrupt as other politicians.”

Not personally corrupt, but uses corruption

A former PAN politician, who was previously on good terms with AMLO, previously described AMLO as not personally corrupt, but someone who “uses corruption” and “encourages corruption” for his political purposes.

Such an example appears in AMLO welcoming politicians with scandalous pasts into his movement – even members of Peña Nieto’s notorious political clan, the Grupo Atlacomulco, which was known for an ethos of mixing politics and business.

“A politician who is poor is a poor politician,” quipped Jorge Hank González, former Mexico State governor and luminary of the Grupo Atlacomulco. The group’s ways were so notorious that the PRI never nominated its members for the presidency until desperate enough to run Peña Nieto in 2012.

AMLO also often seemed selective with his corruption accusations, curiously sparing certain scandal-plagued politicians from his attacks.

Selective corruption accusations

He campaigned in Quintana Roo state in the lead up to the 2016, where accusations of corruption and thuggery against PRI governor Roberto Borge became the issue in the gubernatorial race. Yet AMLO never mentioned Borge in his stump speeches, preferring to assail the usual suspects instead: former president Felipe Calderón, then-president Enrique Peña Nieto and a pair of PAN-PRD gubernatorial candidates, Carlos Joaquín in Quintana Roo, and Miguel Ángel Yunes Linares. (More on both former governors below.)

AMLO also promoted a former príista with a checkered past for governor in Quintana Roo rather than a candidate with a history in his MORENA movement. A source in the state described a scenario in which AMLO ran a weak candidate, attacked the governor’s opposition and promoted a smaller party candidate to split the anti-PRI vote – though the scheme failed as the PAN-PRD won Quintana Roo and PAN took seven of 12 gubernatorial races.

Joaquín, who won the Quintana Roo governor’s race in 2016, eventually became an AMLO ally. He became one of seven governors from opposition parties to receive ambassador appointments – his in Ottawa – after MORENA won the subsequent election. Critics described the governors as being rewarded for “behaving well” during the elections, allegedly by rolling over – surrendering, in the words of critics – as MORENA took their states.

Another notorious example of anti-corruption politics came with the judicial reform in September. Senator Miguel Ángel Yunes Márquez played a decisive role in the judicial reform’s approval after allegedly being pressured with arrest warrants against family members. He became head of the senate’s finance committee last week. He also officially joined MORENA, though the current MORENA governor of Veracruz (where his father was governor for two years) objected, citing accusations of “money laundering and other crimes.”

Former PRI governor Alejandro Murat, whose family was the subject of a New York Times investigation into foreign owners of luxury properties, recently joined MORENA, too. (AMLO previously called Murat running in Oaxaca proof of a “hereditary and corrupt oligarchy.”)

AMLO the redeemer

The ability for so many impresentable politicians to join AMLO’s movement reflected the former president’s image as a redeemer – a man of moral standing, who can absolve the corrupt and illegal acts of those supporting a higher purpose such as his “fourth transformation.” As journalist Azucena Uresti wrote in El Universal.

“López Obrador not only created a political movement, but went further and built a kind of religion in which a supreme being is venerated: himself. The sinners of the past are absolved by the prophet, who is never questioned by his followers, convinced of his infallibility. Those who were once singled out forget their origins so as not to be banished from the land of power. Because there is no doubt, he is the redeemer.”

Corruption accusations came close to AMLO during his presidency, however, including accusations that a son, Gonzalo López Beltrán, “ran a network overcharging contractors supplying materials for the Tren Maya,” according to The Economist. “Another son, José Ramón, was revealed to have been living in a luxury pad in Houston connected to a contractor for Pemex, the state oil company.” AMLO and his sons have vigorously denied any wrongdoing.

Other scandals largely left AMLO unscathed, such as Segalmex – where money at the food security agency went unaccounted for. AMLO also moved to close Mexico’s transparency institute, INAI, which ultimately occurred under Sheinbaum.

But nothing stuck. So far nothing’s sticking to Sheinbaum, either.

Sheinbaum has tried pulling some of AMLO’s populist tropes. She made a plea of poverty in one of the candidate debates by claiming not to own any properties and only renting – despite a career in politics and academia. Opposition candidate Xóchitl Gálvez called Sheinbaum “bien güey” if that were actually true.

But the election showed Mexicans largely believing Sheinbaum. Gálvez, meanwhile, got hit by AMLO making unfounded corruption accusations against her business activities – part of the Mexican pattern of self-made success bringing suspicions of untoward activity.

Sheinbaum has avoided personal corruption scandals throughout her political career. She may not have the same “aura of honesty” as AMLO. But people believe her government is clean and not stealing from them – or at least it isn’t leaving them without benefits. The anti-corruption image starts at the top and it seems to be sticking.